Ever since I started looking closely at drawings deemed “master drawings” in the first drawings exhibition held at the Louvre in 1962, I have been fascinated by the implications of the power of a line. No matter what period, Renaissance, Baroque, 17th or 19th century, the artist can say volumes merely by a line in a drawing. It does not even need to be a line that is perfect. Frequently lines that are re-drawn, adjusted and reinforced are extremely powerful and eloquent. The line can whisper and hint, it can assert, it can describe, it can evoke or imply. A line, in essence, can take on a life of its own, transmit it to the viewer and empower a dialogue between image drawn and the viewer that can be subtle and long-lasting.

Read MoreClose Focus - Art of the Small /

Amid the swirl of daily life, it has been hard to achieve any drawing. Nonetheless, I reminded myself that even doing tiny drawings is better than nothing. Then I remembered that quote from Donna Tartt's "The Goldfinch", when Theo remarks: "To understand the world at all, sometimes you could only focus on a tiny bit of it, look very close at what was close to hand and make it stand in for the whole."

Read MoreArtists' Insights and Imaginations /

While I was wandering through London’s National Portrait Gallery recently, following the meandering trail through the rooms to view the exhibit Simon Schama curated of the sixty portraits in “The Faces of Britain”, I was totally fascinated. Not only because there were so many portraits, in so many media, of icon faces of recent times, but because a quote kept ringing through my head.It was a statement in a National Geographic Magazine article in August 2014 on “Before Stonehenge”: “Art offers a glimpse into the minds and imaginations of the people who create it.” This seemed to be so appropriate of the art I was seeing as I followed the “Faces of Britain” exhibit as it was scattered (cunningly, I decided!) through the galleries. Not only were the faces diverse, interesting and evocative of the people depicted, but the actual art created spoke volumes too about the artists, their perception of the portrait’s subject and the times in which the work was created in each case.

Read MoreHokusai's Example /

When I was looking a the lovely collection of Hokusai's small and intense drawings in the Museum at Noyers sur Serein, I kept thinking about his enthusiastic approach to drawing. A brief quote of his about drawing, "Je tracerai une ligne et ce sera la vie", seems such a lofty goal to which to aspire as a draughtsman or woman. It stopped me in my tracks, because it implies such a deep, wide approach to making marks and creating a drawing. The quote in fact is part of a much larger and famous statement Hokusai made about drawing. Hokusai Katsushika, the long-lived and richly productive Japanese artist whose most famous series of woodcuts is probably the Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji, lived many iterations of an artist's life from his birth about 1760 to 1849. He drew obsessively.

Read MoreAn Artist's Sense of Humour /

The name of the great 17th century French artisan , André-Charles Boulle, is synonymous with astonishingly complex marquetry veneers of woods, tortoiseshell, pewter and brass applied to elaborate furniture of huge value. I never expected to laugh out loud as I was viewing some of his work. I had always associated him with the work he created for Louis XIV and other illustrious French courtiers. He had been designated a master cabinet maker in 1666, by the time he was 24 years old; Louis XIV appointed him royal cabinetmaker in 1672, and he was a hugely successful artist.

The Wallace Collection has a large collection of his furniture, and each table, desk, wardrobe, chest of drawers is well worth studying closely. However, I soon decided that Boulle, for all his fame and wondrous skill in marquetery, must have had a sense of fun and humour.

Read MoreMuseum surprises /

Part of the fun of going to a museum is wondering what you are going to learn about that is totally unexpected and utterly fascinating. There is always something that stops one in one’s tracks. In London, I had huge fun recently learning about the most unusual and esoteric of objects in today’s context. How often does one use a tobacco grater today!

Tobacco had first been brought to Europe by Christopher Columbus and his men from Cuba, and by 1528, Europeans in general were being introduced to it, with an emphasis on all its medicinal advantages. The thriving trade helped foster colonization and was also an important factor in the slave trade with Africa. Sir Walter Raleigh supposedly brought the Virginia strain of tobacco to England in 1578 and again, its healthful aspects were emphasized. Virginia became a very important source of tobacco, with its cultivation spreading to the Carolinas. Tonnage imported to England steadily increased, and by 1620, 54,000 kg. were produced in Jamestown, Virginia, alone.

Read MoreBurgundy as a State of Mind /

As I return to my less art-oriented daily life after my artist residency at La Porte Peinte in Noyers sur Serein, Burgundy, I realise that the time I have spent there, this year and last year, has subtle results. Something I would almost define as a state of mind.

There has been a curious combination of magical, positive elements to achieve such a state. The set-up at La Porte Peinte, first of all, was felicitious in the extreme for me: I thoroughly enjoy being with Michelle and Oreste Binzak who own and run LPP. They are delicious citizens of the world and ensure that artists are made most welcome and comfortable. My room, which I also used as my studio for drawing, was perched high above the Place de l'Hôtel de Ville, the main square in the village, and provided a marvellous sight of what was going on and taking the pulse of the village. My view of timber-framed medieval houses around the square reminded me of those long-distant times during which monks were diligently using leadpoint to prepare their illuminated manuscripts in nearby abbeys whilst other agriculturalist monks were furthering the cultivation of vines and making wines already famous beyond Burgundy.

Read MoreSilverpoint Drawing in Burgundy /

I have decided that I am going to try to have an exhibition somewhere entitled "Let the Stones Speak". Ever since I came to Noyers sur Serein, in Burgundy, last year, I seem to have been having conversations in silver with the most amazing diversity of stones. These stones, too, have been teaching me a great deal about the geology and history of the area. It is a fascinating journey which has led me into wine-making, the history of Cistercian monasteries in this area, mining ocre and early amazing frescoes and paintings, only done in tones of ocre, that can be seen in this area. And on and on. Interspersed with silverpoint drawing in my lovely eerie perch at La Porte Peinte here in Noyers, where I am at eye-level with the swirling, flashing swallows, I have been visiting magical places to learn more about history linked directly or indirectly to my friends, the stones.

Read MoreBurgundy Drawings /

Ammonites de Bourgogne, silverpoint, watercolour, Jeannine Cook

It is done – I have managed to produce 15 drawings for the exhibition at the Musée de Noyers! What a relief! I deliver them next Monday and the exhibition will run concurrently with the show I have hanging at the gallery at La Porte Peinte.

Preparing for an exhibition under deadlines is never a favourite occupation for any artist. However, some people do work best like that. I am not sure that I do – the results of the effort will be for others to judge!

What has been both interesting but also more complex has been the need to weave together a body of work that pertains to the ideas I put forward originally, namely the birth of metalpoint drawing in the scriptora of monasteries, where monks used lead to delineate the illuminations and trace lines for the script of their illuminated manuscripts. Combined with that history, I wanted to celebrate the tiny fossilized oyster shells found in the Kimmelridgian layers of soil found especially in the Chablis area and which contribute to the special terroir of those wines. I had picked up samples of these heavy stones when I first arrived in Burgundy last year, and they have led me on a fascinating odyssey.

Tying the metalpoint’s history together with the fossil-laden stones was thanks to those industrious monks who in medieval times also helped to spread the cultivation of wine, as they founded the great monasteries in Burgundy. Vezelay, Fontenay, Pontigny: they are all centers of such a rich heritage.

Even the wonderful and mighty plane trees, such as one sees at Fontenay that was planted in 1780 by the Cistercian monks, ten years before they had to leave their monastery, was part of that long-standing monastic heritage that enriches us all.

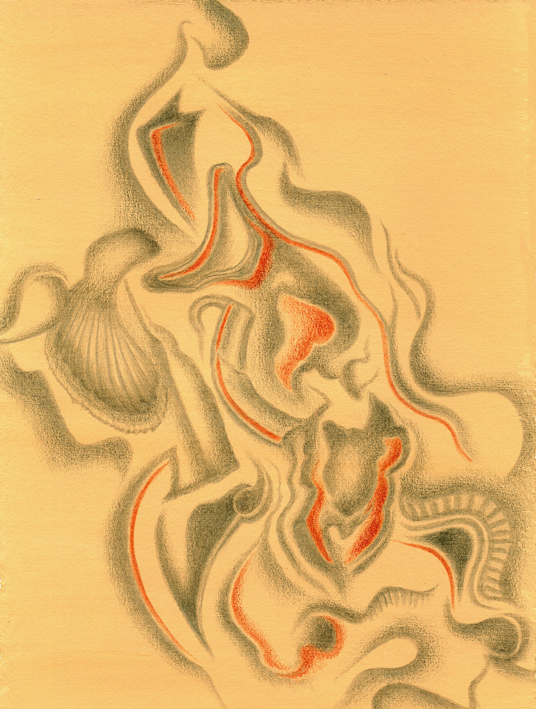

The other aspect that I tried to incorporate into these drawings is the close links between Burgundy and ocre, one of the key pigments in man’s artistic endeavours since the earliest marks man-made on cave walls from Australia to Africa to Europe. Burgundy was famous for its yellow ocre deposits and only ceased to produce ocre pigments in the 20th century. By heating yellow ocre, red ocre is produced; the two pigments find their way into every drawing and painting imaginable down the ages. I used the two colours as tinted grounds for some of the drawings I did for this project. Since early times, some artists used tinted grounds for their metalpoint drawings, so again, I was following a long-standing tradition.

I loved finding out all sorts of things about history and aspects of beautiful Burgundy for this project. It has been such fun - the drawings have been the perfect vehicle and excuse for all sorts of new insights and investigations. It is marvellous when art and fresh knowledge can go hand in hand.

When Art opens Doors /

Vineyard in the Yonne, Burgundy

It is always delicious when you stray into new areas of knowledge by chance. Preparing for my September show at the Musee de Noyers came about because of finding fossil-laden stones last summer and starting on a whole new drawing odyssey. That in turn has opened doors of fascination. I have learned a little about Chablis wines, the effect on their terroir from these minute fossilized oysters in the Kimmelridgian layers of chalky soil and the history of wine growing in that area of Burgundy, in the Yonne department.

Way back in time, wine-bearing vines were cultivated in the regions of Armenia, Georgia and Colchis in 3000-2000 BC. Their culture slowly spread into Europe. These vines were the survivors of devastating ice ages, when Europe was a frozen desert for temperate plants. They had only survived in one area, sheltering on the eastern shores of the Black Sea, protected from the northern and western cold area. After the Ice Ages, the grapevine began to spread again, and felicitously, the varieties of grape that colonized Europe were of high wine-making quality.

In the Yonne department of Burgundy, the oldest traces of wine growing were found on a Gallo-Roman low-relief carving of a harvester picking a bunch of grapes. It dates from the second century AD in the Auxerre region.

By 1323, wine was being produced in the Chablis area, thanks to the efforts of the Cistercian monks at the Abbey of Pontigny. Vineyards were steadily planted in the Yonne because the network of rivers and waterways facilitated the transport of wine to Paris. It was not only the monks in the monasteries who appreciated good wine!

Before phylloxera devastated the wine industry in the late 19th century, the Yonne was the largest wine-producing region in France, with 40,000 hectares under cultivation. Today, there are only about 6,200 hectares of grapes in the Yonne, including about 5000 hectares of Chardonnay grapes grown in the Chablis area.

Just one of the doors to fascination that opened, thanks to my art-making in Noyers. Next post to come, another area I learned about.