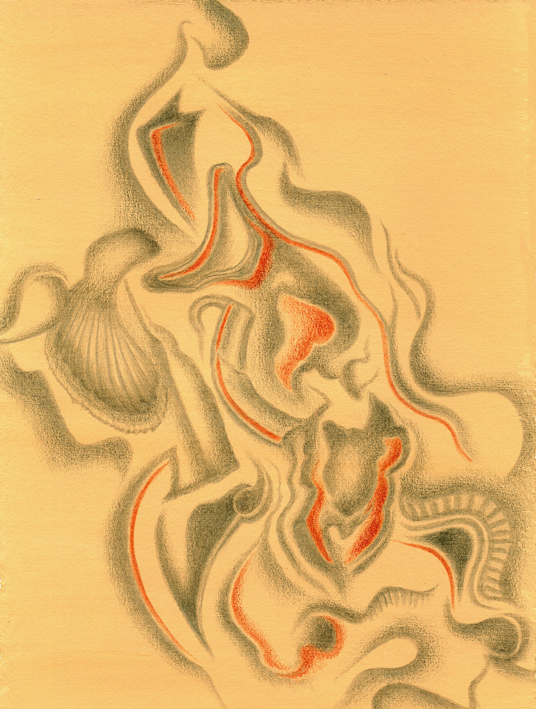

Ammonites de Bourgogne, silverpoint, watercolour, Jeannine Cook

It is done – I have managed to produce 15 drawings for the exhibition at the Musée de Noyers! What a relief! I deliver them next Monday and the exhibition will run concurrently with the show I have hanging at the gallery at La Porte Peinte.

Preparing for an exhibition under deadlines is never a favourite occupation for any artist. However, some people do work best like that. I am not sure that I do – the results of the effort will be for others to judge!

What has been both interesting but also more complex has been the need to weave together a body of work that pertains to the ideas I put forward originally, namely the birth of metalpoint drawing in the scriptora of monasteries, where monks used lead to delineate the illuminations and trace lines for the script of their illuminated manuscripts. Combined with that history, I wanted to celebrate the tiny fossilized oyster shells found in the Kimmelridgian layers of soil found especially in the Chablis area and which contribute to the special terroir of those wines. I had picked up samples of these heavy stones when I first arrived in Burgundy last year, and they have led me on a fascinating odyssey.

Tying the metalpoint’s history together with the fossil-laden stones was thanks to those industrious monks who in medieval times also helped to spread the cultivation of wine, as they founded the great monasteries in Burgundy. Vezelay, Fontenay, Pontigny: they are all centers of such a rich heritage.

Even the wonderful and mighty plane trees, such as one sees at Fontenay that was planted in 1780 by the Cistercian monks, ten years before they had to leave their monastery, was part of that long-standing monastic heritage that enriches us all.

The other aspect that I tried to incorporate into these drawings is the close links between Burgundy and ocre, one of the key pigments in man’s artistic endeavours since the earliest marks man-made on cave walls from Australia to Africa to Europe. Burgundy was famous for its yellow ocre deposits and only ceased to produce ocre pigments in the 20th century. By heating yellow ocre, red ocre is produced; the two pigments find their way into every drawing and painting imaginable down the ages. I used the two colours as tinted grounds for some of the drawings I did for this project. Since early times, some artists used tinted grounds for their metalpoint drawings, so again, I was following a long-standing tradition.

I loved finding out all sorts of things about history and aspects of beautiful Burgundy for this project. It has been such fun - the drawings have been the perfect vehicle and excuse for all sorts of new insights and investigations. It is marvellous when art and fresh knowledge can go hand in hand.