As I looked at portraits of 17th century Spanish royal ladies in the Prado, they suddenly offered a fascinating sampling of how women fasten their dresses. Not for them a simple method of closing their dress. Rather, the fastening became part of the bold, imaginative design of the gown, part of the message of power, wealth and circumstance that was so dazzlingly recorded in paint by Court painters.

Read MoreSpain

Plein Air Art - Looking Back (Part 5) /

When John Singer Sargent painted this scene of Claude Monet working en plein air, he recorded the heyday of the Impressionists' love of working outdoors to record and celebrate nature. Ever since, there has been a long list of wonderful plein air artists on every continent, and we artists, living today, have a rich heritage of landscape art from which to be inspired. This is the final Part 5 of my blog entry on Plein Air Art- Looking Back.

Read MoreHow Artists' Work Evolves over the Years /

Does an artist remain faithful to early visions and inspirations for art creation over the passage of twenty-five years? Measuring my own evolution, I find that I have just moved in closer to look at the nature that surrounds us, to marvel at details that often get overlooked in our busy lives.

Read MoreCelebrating Women - Roman Style /

It seems that every single exhibition to which one goes is a new source of fascination - a good reason, I have decided, to bestir oneself and get to different shows. "Women of Rome", from the Louvre Collections, is just such an example. On exhibit in Palma de Mallorca, Spain, at the Caixa Forum until 9th October, it examines the images of women portrayed in Roman times.

Read MoreLandscapes /

The snow had fallen all night, but the morning dawned clear and sharp. To the south, as I topped the first rise of the hills, lay the Pyrenees, higher, more intricate in form and peak, more immense in span of horizon than I remembered. My second time as an artist in residence at Bordeneuve was beginning in beauty. Some of the peaks were blushed pink-apricot, others were subdued in greys and pearls. The foreground of rolling, energy-filled hills was their prelude, dark with winter filigree of trees. This massive display of seemingly timeless mountain ranges, so memorable, so old, so sacred and so wildly beautiful, left me with mixed emotions. I could understand why early man used the Pyrenees mountain caves and dwelt in these abodes close to their food sources and to their gods.

Read More"A-ha" Moments in Exhibitions /

Do you ever experience a wonderful moment when you see something in an exhibition, it suddenly resonates and explains some connection, or gives an unexpected insight into something else? I love those moments. I had a few such instances during my exhibition "orgy" in London recently. The first one came as I was marvelling at Goya's drawings in the superb "Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album" at The Courtauld Gallery. This exhibition was the first reconstruction of the dispersed 23 drawings from Francisco Goya's so-called Album D, "Witches and Old Women, produced during the wonderfully productive last decade of his life, together with other related drawings and prints.

The exhibition was riveting in every way - Goya's economy of drawing, his powers of depicting human emotions in their most raw and dramatic forms, his mordant commentaries on human foibles, all so simply done on small sheets of paper, in shades of ink - oh heavens! The scholarly work done that permits the reconstruction of this album, in a coherent and likely order of drawings, was also most fascinating and impressive.

Then, in the works accompanying the 23 drawings, there was a brush and brown ink drawing from Album B, Estas Brujas lo diran (Those Witches will tell).

I was so astonished. The line from Goya ran straight and true to Egon Schiele's Self Portraits. Goya's drawing is a haunting image of a naked old witch devouring snakes. Egon Schiele's Self-Portraits tell of equally disturbing solitary states of mind.

Both artists are fluid in their lines, their vigorous treatment of wet and dry passages of drawing media. Did Schiele know of Goya's drawing in the Prado? Or was it just happenstance, the result of two gifted draughtsmen's states of mind?

Another "aha" moment for me that stands out in my memory was when I was looking at one of several unusual Claude Monet paintings in "Inventing Impressionism: Paul Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market" at the National Gallery. In the gallery showing works by Monet that Durand-Ruel had exhibited in a pioneering monographic show in 1883, , there was an arresting painting of two apple tarts or galettes on wicker platters, Les Galettes, painted in 1882 and in a private collection today.

Its vigour and brio of treatment, its golds and yellows and close-cropped composition all take one straight to Vincent Van Gogh and his sunflowers or even a study of humble fishes, or bloaters. Did he see Monet's study of the Galettes - he most probably did, as he produced the first studies of cut sunflower heads some five years later.

The third moment of fascination for me was in the same Impressionist exhibition, again a Monet painting done in 1875, The Coal Carriers. Monet had seen workers unloading coal for the Clichy gasworks from the train from Argenteuil to Paris, and painted this work partly from memory.

The rhythmic placement of the men on the gangplanks, the silhouettes and dark colours somehow reminded me of many of the Japanese ukiyo-e prints, their rhythms and cropped views. Monet was an avid admirer of the new wave of Japanese prints coming in to Paris at that time.

I love these moments when you can link up artists, influences and inspirations. They validate one's own endeavours as an artist as you study and view other artists' works, not to copy, but to use as pathways to grow and spread wings.

The Symbolism of Words /

When I first came to Mallorca, Spain, so many years ago, it was still during Franco's regime. The Balearic Islands were officially forbidden from speaking their own regional language, Mallorquin, and they certainly were not allowed to have any symbol like a regional hymn.

Slowly, slowly, over the years after Franco died and Spain became a democracy and part of the European Union, the Balearics regained their identifying characteristics. One of the most beautiful aspects, I have always thought, was the song that is now termed the hymn of Mallorca, La Balanguera.

The poem that gave rise to this hymn was written by Joan Alcover i Maspons, as a children's poem that combined whimsy, beauty and instructional philosophy for their life ahead. The poem was put to very lyrical music written by the Catalan composer, Amadeo Vives, and in 1996, the appropriate governmental body, the Consell de Mallorca, declared it to be the island's official hymn.

I have always known, of course, its Mallorcan or Spanish versions, loving it when I hear its melodies sung or even hummed. I recently found an English version translated by Dr. George Giri and published in the Majorcan Daily Bulletin.

Its words contain enough quiet wisdom that I think they bespeak a beauty worth considering.

The spinning wheel’s mysterious treadler Like a spider its subtle art Reels away her flaxen distaff Into yarn that holds our life Thus the spinner treadles On and on And spins her yarn.

Turning glances backward Sees the shadows of the past And the coming springtime Hides the seeds of things to come Knowing that the roots are growing And new roots are taking hold Thus the sinner treadles on and on And spins her yarn.

Hopes that hold traditions Weave a banner for the young Like a veil for future marriage Locks of silver and gold Which are spun into our youth But with age are nearly gone Thus the spinner treadles on and on And spins her yarn.

The Spanish version is just as lyrical in feel.

La Balanguera misteriosa (del francés "boulangère": panadera), como una araña de arte sutil, vacía que vacía la rueca, de nuestra vida saca el hilo. Como una parca que bien cavila, tejiendo la tela para el mañana. La Balanguera hila, hila, la Balanguera hilará.

Girando la vista hacia atrás vigila las sombras del abolengo, y de la nueva primavera sabe donde se esconde la semilla. Sabe que la cepa más trepa cuanto más profundo puede arraigar. La Balanguera hila, hila la Balanguera hilará.

De tradiciones y de esperanzas teje la bandera para la juventud como quien hace un velo de bodas con cabellos de oro y plata de la infancia que trepa de la vejez que se va La Balanguera hila, hila, la Balanguera hilará.

Hymns always reflect the optic of the region or nation that has them. The gentle yet fatalistic recognition of life's realities inherent in La Balanguera is very congruent with the sense of long history and solid self-identity with which this island faces the invasion of visitors and potential foreign residents over the years. I love this feeling of deep-seated culture that underpins Mallorcan life in so many instances, especially away from the tourist centres.

In essence, La Balanguera tells of the art of living. An interesting choice for a hymn.

The Stilling Voice of Art amid the Hurly Burly of Airports /

I am always surprised by the sudden shock of rounding a corner in a busy airport and finding a moment of centering peace. It does not happen often, but when it does, it makes the travelling more bearable in today's abrasive airports.

It happened recently to me again. Atlanta's relentlessly busy, noisy airport had offered a few moments of quiet amid the pounding feet, with an exhibition of children's art on the walls of the international flight concourse E. The voices of these paintings sang of hope and joy, a contrast to the often intent and stressed faces of fellow travellers.

The really lovely moments of peace from art came in Madrid, an airport which has grown organically and offers many versions of art from different building phases of the airport. Even ceilings are well designed, as shown in Perec's lovely photo taken in Terminal 4 that opens this blog post.

One huge merit of the airport is that there are no public announcements and the universal quiet is already a balm. Add to that the art, especially in some of the VIP lounges. It is quietly elegant in voice. You turn a corner and there is a collection of modern prints, discreet and well presented. Their effect stills and composes. You suddenly find the energy to go on with your trip, renewed in some subtle, indefinable way.

As you press on to the gate for your next flight, little prayers of thanks to those artists float up to the skies. Art - of so many different descriptions - fills our lives with richness and healing. It gives me hope for safe landings.

Joaquín Sorolla and the Sea – Part II /

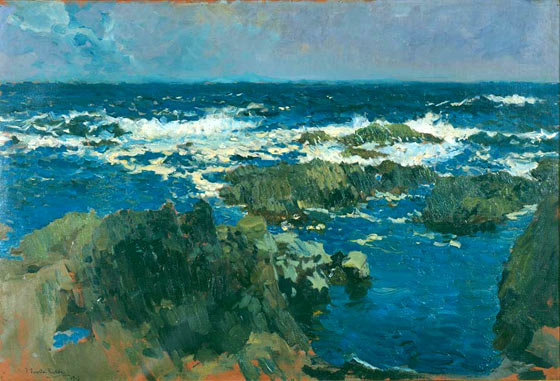

My last blog post was on Joaquín Sorolla's approach to plein air painting, after I saw the CaixaForum exhibition, "The Colour of the Sea" in Palma de Mallorca. His "Colour Notes" are so fresh and searching, so bold and gestural, that I sometimes felt that the resultant paintings, in which this carefully observed material was incorporated, lost a little in impact. Nonetheless, the exhibition shows beautifully how Sorolla, set up on the beach in very practical painting fashion, was ever-intent on capturing the endless changes of the seascapes. His meticulous studies of the different hues of blue, for instance, show his passion for capturing the limpid colours of the sea, the play of light on the waves or on bodies in the water, their diversity of tone. Yes, he was basing all his art on Nature, in a realistic fashion, but he certainly was breaking down what he saw into the most abstract of shapes and compositions.

Look, for instance, at the Young Swimmers. Their skin underwater becomes a shimmer of alabasters floating in this energy-filled abstraction of green ripples and dancing light.

Another canvas that interested me in the flattening of the perspective is Marie at the Beach. As in other paintings he did of contrejour light on cliff tops, Sorolla flattened out the distances: the sea below is virtually on the same plane as Maria, because one senses his total fascination with the sea and its restless play of light and foam.

The translucence of white fabric, seen contrajour against the sea, is another of his favourite subjects. Just out of the Sea demonstrates this marvellously; it is all about that luminous, undulating light blowing in the wind, contrasting with the glowing solidity of the mother and small boy, all rendered tangy in the salt air and the susurration of the turquoise sea.

The marine landscapes are all about luminosity, distance being dissolved into pure colour. Sky and sea are his fascinations, his challenges. No wonder he stated, ""I could not paint at all if I had to paint slowly. Every effect is so transient, it must be rapidly painted.”

His 1919 works done at Cabo San Vincente in Mallorca are pure colour hymns. No wonder he is loved by so many for these celebrations of the sea, one of Spain's greatest beauties in his lifetime. We are lucky that he recorded his country's coastal scenes before they were transformed by 20th-century mass tourism.

Joaquín Sorolla and the Sea - Part I /

An exhibition, "Sorolla: The Colour of the Sea" has just come to Palma de Mallorca via the CaixaForum, having travelled to various cities in Spain in larger or smaller version. The paintings and oil on board studies have been lent by the Sorolla Museum in Madrid. They reflect Joaquín Sorolla's passion for the sea, despite the fact he was not born at the coast. They also testify to his enormous skill in working en plein air, at great speed, trying to be faithful to the every-changing light, the restless sea in all its moods and the feel of the place in which he was painting.

Sorolla commented, "Me sería imposible pintar despacio al aire libre. No hay nada inmóvil en lo que nos rodea. El mar se riza a cada instante, la nube se deforma, al mudar de sitio – pero aunque todo estuviera petrificado y fijo, bastaría que se moviera el sol, lo que hace de continuo para dar diverso aspecto a las cosas. Hay que pintar de prisa porque cuanto se pierde, fugaz que no vuelve a encontrarse!”. Roughly translated, Sorolla said that it was impossible for him to paint slowly en plein air. Nothing stays still around us. The sea ripples continuously, clouds change their form as they move, and even if everything were totally still, even cast in stone, everything would still change in aspect because the sun moves all the time. You have to paint quickly because so much gets lost, some much is fleeting and will never return.

Any artist who has worked outdoors knows exactly what Sorolla was talking about.

The exhibition showed a fair number of oil on cardboard, small studies, "Colour Notes", and for me, they were the most fascinating aspects of seeing the show. In this first blog entry on Sorolla, I will concentrate on them, as far as I am able to find decent images. First of all, you see Sorolla responding to Nature's colours and forms and seeking the fleeting approximation of the colours and light that he saw. These small rectangles of colour impressions are so abstract it is amazing, even though Sorolla was a passionate Realist.

Since the sea is endlessly in motion, it is astonishing how Sorolla captures its moods and movement, particularly considering that he did not spend all his time at the coast. His early visits to the brilliantly-lit Mediterranean areas near Javea and Valencia were later contrasted with visits to the north at San Sebastian and Biarritz, with very different atmospheric and marine conditions.

The studies and paintings of the sea are, to me, the most wonderful part of Sorolla's opus. For him, of course, these studies were the preparation for the larger finished paintings. He knew that understanding a scene, preparation and prior choice of colours all helped when it came to working on a bigger canvas. He remarked, "The great difficulty with large canvases is that they should by right be painted as fast as a sketch. By speed only can you gain an appearance of fleeting effect. But to paint a three yard canvas with the same dispatch as one of ten inches is well-nigh impossible.”

Nonetheless, Sorolla also knew that once he got going, all bets were off on how the painting would evolve, because the light, scene, sea, would be continually changing. He advised, “Go to nature with no parti pris. You should not know what your picture is to look like until it is done. Just see the picture that is coming."

For him, as for every artist, especially one working en plein air, every work was a gamble. In his case, however, his gambles paid off handsomely most of the time.