Visiting master embroiderer Alain Dodier in Sainte Valiere, Southern France, was like straying into a medieval scriptorium, save that Alain is very much of our time Nonetheless, as he creates intricate vivid scenes in silk embroidery threads, using Bayeux stitching that harks back to the 11th century, his passion and dedication to historical detail and fidelity reminded me of the slow and painstaking creation of illuminated manuscripts that tell stories of great import to Western culture. His seven-meter panel about the Pilgrims’ Route to Santiago de Compostela is one such work.

Read MoreArtistic Dedication

A Passion for Drawing /

Three exhibitions in New York, each by a superb artist in a different century, but all united by a lifelong passion to draw, draw, draw, anything and everything. For an artist, these current exhibitions are a wonderful reaffirmation of the central role drawing potentially plays in the development and creativity of an artist. Gainsborough, Delacroix, Wayne Thiebaud - three very dissimilar artists, yet they are all on the same page in a drawing book.

Read MoreArtists' Dedication /

The other day, a friend remarked to me that in these lean economic times, we will see important works of art and literature being produced. In other words, artists, almost in spite of themselves, will be working away, and the challenges they face will be a stimulus to go further, do things differently and make progress.

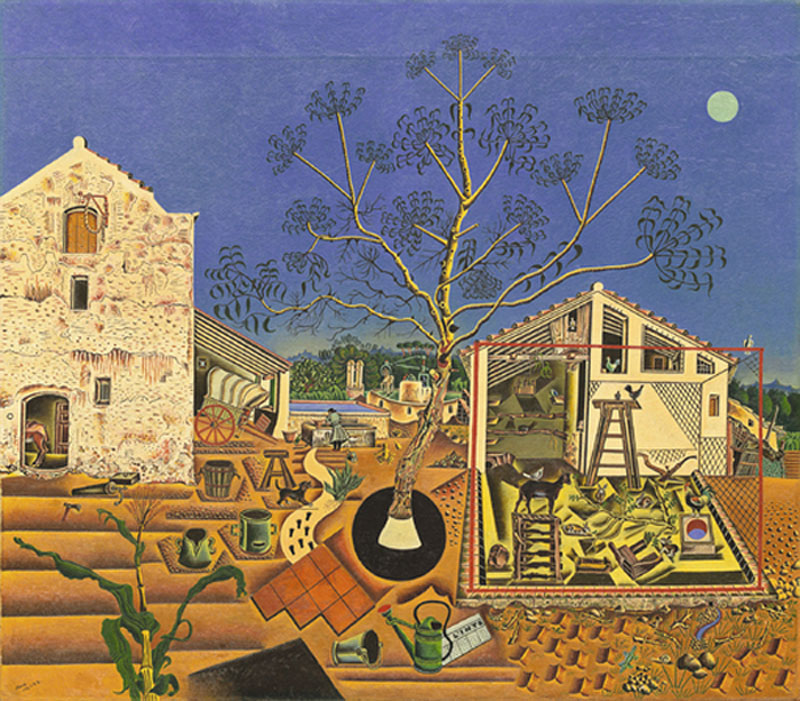

This dedication to art-making was, for instance, an early characteristic of Joan Miro . As early in his career as 1915, he quoted Goethe's statement that, "He who always looks ahead may sometimes falter, but he then returns with new strength to his task". At that time, Miro was principally dedicated to landscape painting, and was soon to produce some of his early masterpieces about life at Mont-roig, his family home in the Tarragona countryside, near Barcelona.

House with Palm Tree, 1918, Joan Miró. (image courtesy of the Reina Sofia Museum, Madrid)

L’ornière, The Rut, 1918, Joan Miró, Private Collection

Vegetable Garden and Donkey, 1918, Joan Miró, (Image courtesy of Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden

The Farm, oil on canvas, 1921, Joan Miró (image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC),

These four paintings are all results of what Miró regarded as trial and error work. He admitted to stumbling as he tried to deal with his depiction of the countryside, but he always got "to his feet again". This determination to "return with new strength to his task" remained with him during his long and artistically very inventive life, despite the difficulties he experienced personally or because of his opposition to Franco and his regime in Spain. (A marvellous celebration of Miró's dedication to art, "The Ladder of Escape", can be seen in Barcelona at the Fundacio Joan Miro from 13th October, 2011 to 25th March next year. It has just closed at the Tate Modern, London.)

Every single artist hesitates, stumbles, doubts and abandons one path for another. Only those who have enough inner fortitude, a strong enough conviction that they must continue with their endeavours, are people whose creativity leaves a mark in our world. When there are really difficult times, economically, politically or personally, it becomes a real test of an artist's dedication that he or she continues to work and produce. We are living in such times. It will be interesting to see - in a few years' time - whether my friend's prediction about stellar work being produced in today's world is accurate.

More Thoughts on Creative Passion /

I was fascinated to listen, this morning, to Krista Tippett's programme, Speaking of Faith, during which she was interviewing Adele Diamond, a cognitive developmental neuroscientist who currently teaches at the University of British Columbia in Canada.

During the wide-ranging conversation, Dr. Diamond alluded to passages of various books which she had assembled in a book to present to the Dalai Lama whom she saw at Dharamsala, India, during a Mind and Life Institute dialogue. She cited one that made me reflect on what I had been saying in my blog yesterday about passion driving artists in particular. She quoted Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel from his book, "God and Man" and whilst the passage talks of a poet or a musician, the excerpt applies absolutely to visual artists too.

"Deeds set upon ideal goals, deeds performed not with careless ease and routine but in exertion and submission to their ends are stronger than the surprise and attack of caprice. Serving sacred goals may change mean motives. For such deeds are exacting. Whatever our motive may have been prior to the act, the act itself demands undivided attention. Thus the desire for reward is not the driving force of the poet in his creative moments, and the pursuit of pleasure or profit is not the essence of a religious or moral act. (My emphasis.)

At the moment in which an artist is absorbed in playing a concerto the thought of applause, fame or remuneration is far from his mind. His complete attention, his whole being is involved in the music. Should any extraneous thought enter his mind, it would arrest his concentration and mar the purity of his playing. The reward may have been on his mind when he negotiated with his agent, but during the performance it is the music that claims his complete concentration. (My emphasis again.) Man’s situation in carrying out a religious or moral deed is similar. Left alone, the soul is subject to caprice. Yet there is power in the deed that purifies desires. It is the act, life itself, that educates the will. The good motive comes into being while doing the good.”

What caught my attention was the issue of being totally involved in the act of creation, and not thinking of anything else like monetary reward, for instance.

Self-Portrait, 1659, Rembrandt (Image courtesy of the National Gallery)

Self-Portrait at the age of 63, Rembrandt.1669, (Image courtesy of the National Gallery)

So often one hears of artists caught up in having to paint in a certain fashion because previous versions of the painting/drawing or whatever have sold well, and pretty soon, the art being created ceases to have the same impact and nears the situation of "pot boiler". Yes, of course, there are definitely economic considerations, especially now, but nonetheless, there is always this danger lurking of "arresting concentration and marring purity". In other words, the passion for creation has been dissipated.