Visiting Pech-Merle Cave in France has been on my wish list for a long time, and this week, I achieved the wish.

What an amazing place and what a heritage we artists have in these cave drawings that early man created on the rock walls!

Location Map of Pech-Merle Cave, France

There is an astonishing mixture of the most beautiful stalagmites in columns, fans and banks with these seemingly smooth rock faces where those distant artists left their marks.

Enormous chambers, still dripping with moisture and forming more beauty in the limestone, have a sense of the spiritual, despite the fact that visitors are in groups, shepherded along by a guide.

Pech-Merle Cave

There is almost too much to see and absorb, too many shapes and formations to encompass; one longs to be able to slow down and linger. Alas, that is impossible because there is a limit of 700 visitors a day to try and conserve the freshness of the art work.

The cave was blocked by rock falls for many thousands of years, which helped conserve the drawings better than in other caves. Thus there is the obvious concern to keep them in a good state of conservation.

Those early, few artists were determined people. It is hard to imagine the effort it must have required before they even traced the first line on a rock face. Cro-Magnon man lived in the fertile Lot river valley far below. There, the artist must have first had to prepare charcoal in stick form or grind red ochre into powder, fine enough to be blown through a small tube. Then he (judging from the content of the Pech-Merle drawings, it had to be a “he”!) had to climb up the steep hills to gain entrance to the cave. Before scrambling into the cave down narrow, tortuous openings, he had to ensure he had enough, reliable light from his flickering, open flame torches. Then, once inside the chambers, he had to select a rock face he could reach, that was not too damp and that lent itself to the images he planned to draw.

Even the rock surface was rough, not an easy surface for mark-making. One of the remarkable aspects of cave art is that there are layers upon layers of work. Art was executed on the same surface with thousands and thousands of years in between. In Pech-Merle, the first frieze of black drawings – bison, mammoths, horses of extraordinary vigour and freedom, probably all done by the same artist – has red iron oxide dotted markings beneath that are thought to be done some 8000 years previously.

Early Blown Pigment Hand Outline, Pech-Merle Cave

Mammoths and Horses - Black Frieze, Pech-Merle Cave

Young Mammoth, detail of Plack Frieze, Pech-Merle

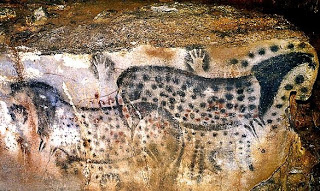

The most famous of Pech-Merle’s rock paintings, the Dotted Horse Panel, is vast and breath-taking. I was lucky enough to happen on it a few minutes before the rest of our group, and being alone to contemplate this extraordinary complex work allowed a dazzling connection with those long-ago artists.

Dotted Horse Panel, Pech-Merle Cave

Hand outlined by blown pigment, detail of Dotted Horse Panel, Pech-Merle

There was an early, early depiction of a long, spotted fish in red ochre, half obscured by the later drawings of the horses. The artist who conceived of and drew the horses used the configuration of the rocks themselves to incorporate them into the drawing. The outline of the rock suggests the horse’s head and neck, and the drawings flow from there. All the marks were blown stencils of fingers, thumbs and hands – all used to further the depiction of these two stylized horses with their powerful bodies and diminutive legs with dots big and small. The work bespoke of a clarity of vision and execution that would defy most people today with far, far better working conditions. Remember, flaming torches only have a finite time to burn, for example.

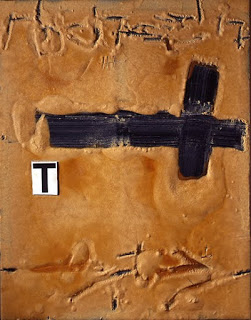

What also fascinated me in Pech-Merle was that those early, early artists not only celebrated the animals of their world, but they also made abstract drawings – triangles, strange symbols… - as well as very stylized depictions of women, even bison-women.There is also a poignant stylized man, lying mortally wounded with spears traversing his body, near a geometrical symbol.Interestingly, it is thought that artist travelled some 40 kilometers to another cave to draw the same type of wounded man, with a similar symbol, but not directly adjacent to the man as it is in Pech-Merle.

Wounded Man and Geometral Sign, Pech-Merle Cave

I suspect that every visitor to Pech-Merle emerges into the light of day dazzled and enthralled.

The mind-stretching sense of time and connectedness to those astonishing artists left me humbled and yet almost exalted at the thought of the heritage we artists share with those mark-makers working some 25,000 years ago.