This morning I was listening to NPR Saturday Edition when Scott Simon interviewed New Republic film critic, David Thomson, about his new book, Moments that made the Movies. During the conversation, Thomson talked about the power of quiet moments, or looks or lines, in films that are remembered long afterwards - think Casablanca, for instance. Thomson went on to say that during those quieter moments, we are more able to think ourselves into the scene as viewers, shaping our perception of the film, and thus, later, remembering those moments more vividly than more action-packed scenes.

The conversation made me reflect that in essence, the same reaction often occurs in the visual art world, as each of us walks through a gallery or a museum, looking at art work. For me personally, many of the works that remain with me, long afterwards, are not the paintings of "sturm und drang", the high voltage works that leap off the walls. Instead, indeed, the quieter works have more resonance, more power to stay with me and come floating back into my mind's eye to delight again. Obviously, each of us has a different character, different tastes and a different life experience which we bring to the viewing of the art. Nonetheless, when the art is elegantly quiet, simple and impactful, it often lends itself to being "expanded" by each viewer and allows an "ownership" that then becomes part and parcel of the viewer's experience.

One of the most fascinating examples of a quiet work that I have met is a minute drawing that I have only ever seen in reproduction, Measuring a little over 4 x 3 inches, it is a silverpoint drawing, Horse and Rider, done by Leonardo da Vinci in 1481 as part of a preparative study for his commission of an altarpiece, the Adoration of the Magi, in the Church of San Donato a Scopeto, outside Florence.

This tiny drawing, which was consigned for sale in 2001 at Christie's by the late J. Carter Brown, once Director of the National Gallery in Washington, was so esteemed that it fetched the astonishing price of £8,143,750 ($11,474,544) before transaction costs. Clearly, this is a piece of art that haunts people. Its immediacy, the skill in depicting the foreshortened horse and its motion, its utter simplicity all make it an astonishing piece of art. I know that it is the first piece of art to comes back to me when I begin to think of art that I have long remembered.

Usually, the works of art that have the most impact on me as I go around a museum are ones that I can guarantee will not be readily obtainable as reproductions in postcards, books, etc. I seem to have a gift for liking things that are not the popular ones by museum standards - I don't know what that says about my tastes! However, one remembers, as much as possible, and the magic floats back into my mind at times from those quiet beauties.

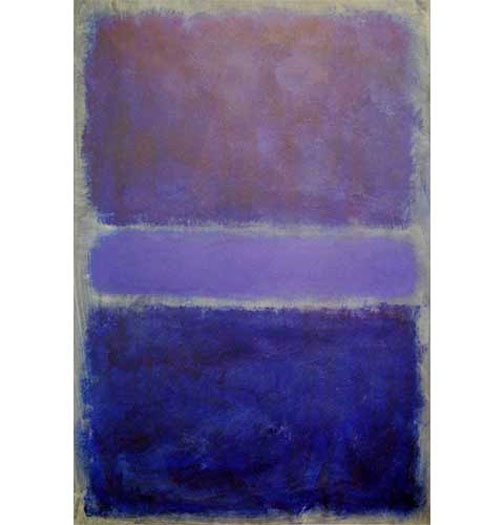

Other works that have retained their influence over me range from Alfred Sisley to Chardin, Fatin-Latour to Rothko and beyond - a totally eclectic mix, I acknowledge.

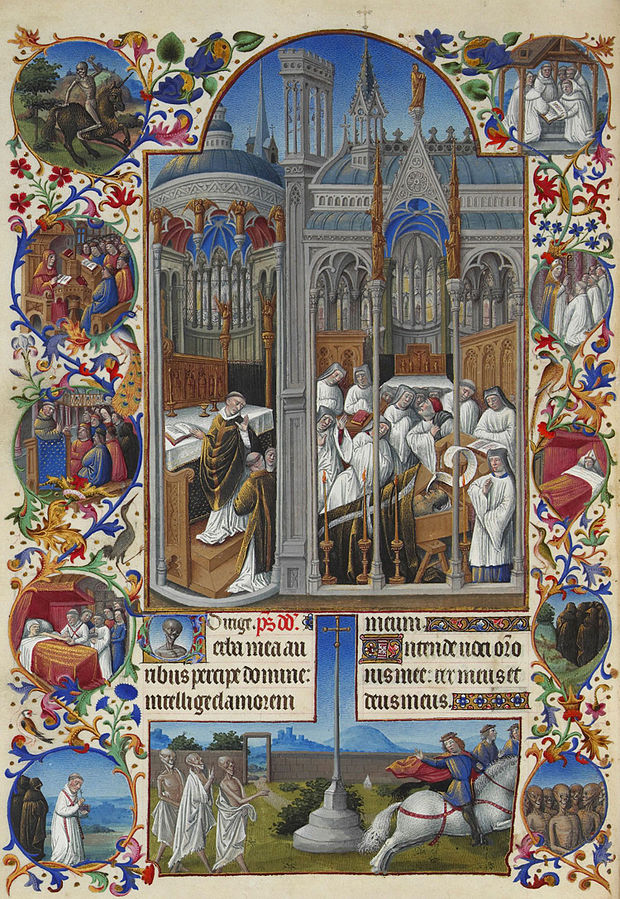

Carafe of Water, Silver Goblet, Peeled Lemon, Apple and Pears, 1728, (Image courtesy of the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe)

Each of us has a different collection of remembered quiet moments when art has resonated and stayed with us. Its diversity and power to uplift, move and inspire come with moments of contemplation and emotion. Those encounters are what make art so extraordinary and so necessary.