Back in March of this year, in The Spectator, Angela Summerfield discussed Peter Frie:Last Summer, an exhibition of landscapes by a Berlin-based Swedish artist, Peter Frie. In view of the fact that tomorrow, I am planning to work plein air on landscape drawings, this statement in Summerfield's article came back to me.

I quote, "Landscape painting has not fared well within the dictates of modernist and post-modernist art definitions. It is as if an urban-centric, text-driven and often anti-aesthetic dogma has stifled both alternative discourse and individual human expression. Yet our experience of landscape, and by association Nature, is fundamental to the development of our senses, perceptual vocabulary and cognitive awareness.

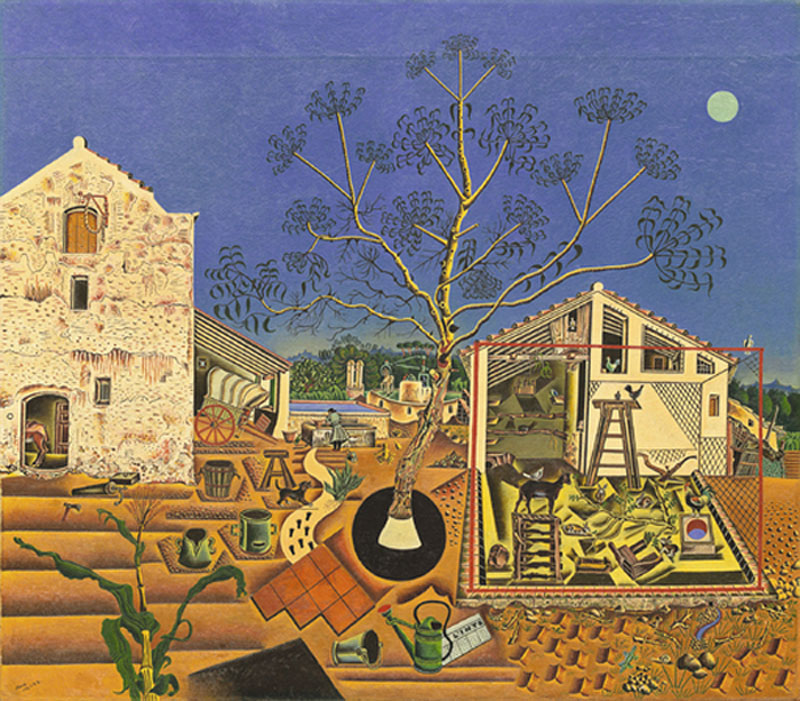

Eliopainting No. 3 Peter Frie, oil on canvas, (image courtesy of Eskilstuna Konstmuseum.)

This statement resonates for me in a number of ways. Since I live in non-urban environments, I find most of my daily delights and inspiration in Nature, in one way or another. I am also very aware that my tastes are therefore different from those of countless millions of people who live in big cities, where the dragooned green trees along streets and in artificially-constructed parks are the major remnants and reminders of the natural world, apart from weather conditions.

The world in which we all live is indeed mostly text-driven, a fact which again contributes, according to this thought-provoking book that I am reading, Moonwalking with Einstein, by Joshua Foer, to our collective loss of the capacity for memory. Because we can all rely on books, Google, digital files or whatever to recuperate facts, our memories have virtually abdicated, as compared to the memory of Greeks, Romans and medieval notables.

In those early times, people could remember vast amounts of knowledge, from all the names of soldiers in an army to long, involved speeches or treatises. After Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1436, our memories took a hit. In the same way, only well-trained artists retained the capacity to remember innumerable details of landscape or human form. Familiarity with landscapes and Nature's ways became the domain of the few in the art world.

Today, that is indeed true. Yet unless we artists somehow learn how Nature "works", an enormous chunk of our personal vocabulary is stunted. It is as if we try to learn French, but never hear how the words are correctly pronounced. We thus never understand the nuances, the cadences and accentuations, let alone the words themselves, that convey a world of meaning.

Ultimately, I fear that Angela Summerfield's rather pessimistic outlook about landscape painting will continue to pertain. I don't see art collectors returning en masse to support landscape painting (and drawing). Nonetheless, for those of us who believe landscapes and Nature in general have much to offer, there is the comfort that personally, we are enriched, and that there are indeed some people with whom landscape painting resonates. Hurray for "alternative discourse and individual human expression"!

Peter Frie's version of a "Blue Morning" (image courtesy of artfinders.co.uk.)

Just look at Frie's Blue Morning. He should give us all encouragement and hope to follow our own paths vis-a-vis Nature.