After I had been writing about the evolution of landscape painting and the attitudes towards it, I was fascinated to stumble on the following quote : "How to paint the landscape: First you make your bow to the landscape. Then you wait and if the landscape bows to you, then, and only then, can you paint the landscape." That was John Marin's observation.

From very early on, he believed in the importance and power of the visible, the need actually to see himself what he was seeking to portray as a landscape. His landscapes were amazingly individualistic and memorable. His "bows" to and from the landscape meant that he truly understood that scene and had processed it through eyes, brain and hand so that it became his own, his own version of it.

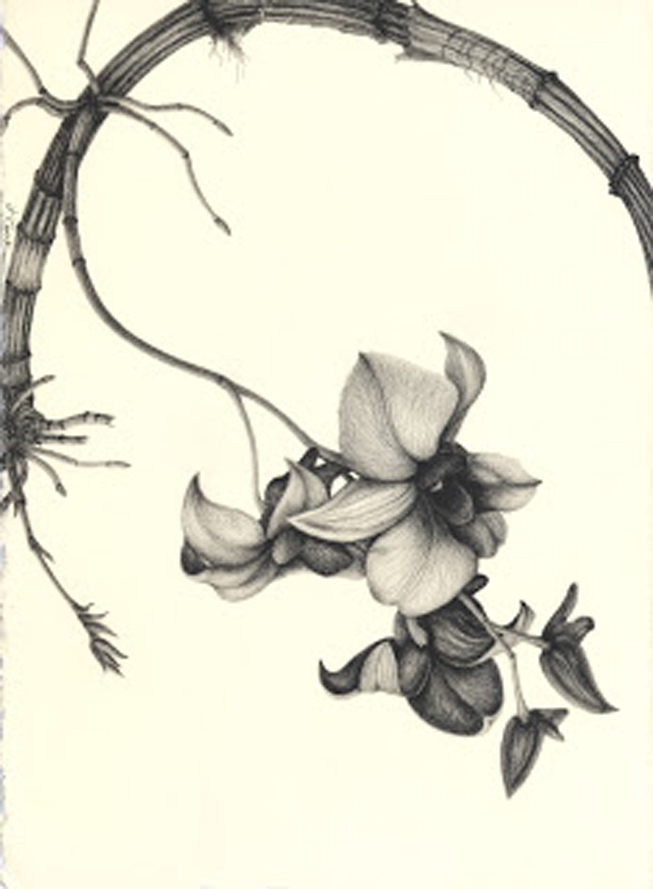

Franconia Range, White Mountains, No. 1, 1927, watercolor, graphite pencil, black chalk, John Marin (Image courtesy of the Phillipes Collection)

Vincent Van Gogh talked in a similar vein about the importance of the artist knowing the landscape well enough to create art about it. He said, "One can never study nature too much and too hard." Like John Marin, his landscapes can never be confused with anyone else's - he distilled what he saw and experienced in a totally individualistic fashion to create marvels.