I alluded in a previous entry to John Marin bowing to the landscape, and if it bowed back to him, he would then feel permitted and able to paint it.

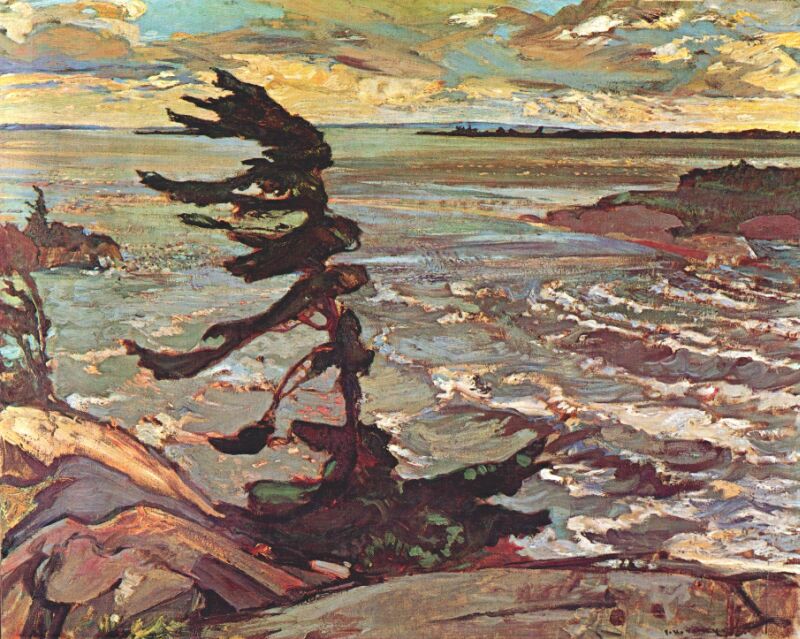

John Marin, Hurricane, 1944. Collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

I was reminded of this again while reading a fascinating book, "Beauty", by Roger Scruton which was published earlier this year by Oxford University Press. Professor Scruton meticulously examines the aspects and characteristics of beauty, point by counterpoint. At one point, he writes, "My pleasure in beauty is therefore, like a gift offered to the object, which in turn is a gift offered to me... the pleasure in beauty is curious, it aims to understand its object and to value what it finds."

That is exactly the way I find myself approaching and reacting to the beautiful landscapes I see here in coastal Georgia, or in Mallorca, for instance Not only does one savour of their beauty per se, but then, as one draws or paints, it is first a quest to see carefully and understand better what one is experiencing. Somehow, one needs to "process" all this information internally, almost intuitively, and then try to transmit the results of this wordless dialogue to paper, in one's own style and idiom. Scruton goes on to talk of the fact that only humans can look at - say - a landscape in an alert, disinterested way, "so as to seize on the presented object, and take pleasure in it".

Perhaps that is one of our privileges as humans. But it is also much easier to talk or write about apprehending the gift of beauty in landscapes than actually "bowing" back to the landscape as an artist and producing a decent work of art!