Yesterday I spent time again at the Telfair Academy in Savannah, looking at Dennis Martin's amazing metalpoint drawings, in preparation for a silverpoint workshop I am giving there today.

One of the aspects that has fascinates me about Martin's approach to drawing is his superb use of lost and found edges. By this, I mean his method of making a transition from a contour line to shadows and ill-defined edges of an object. The defining line gets lost, then reappears again, and the overall effect allows for a very satisfying, yet often mysterious integration of subject matter into a background, for instance. He uses a mixture of goldpoint, platinumpoint and graphite, all media that do not change colour (unlike silver which tarnishes eventually in the marks on paper), and thus they can be used as three different values that can seamlessly move from very light to much darker, even extreme darks of graphite.

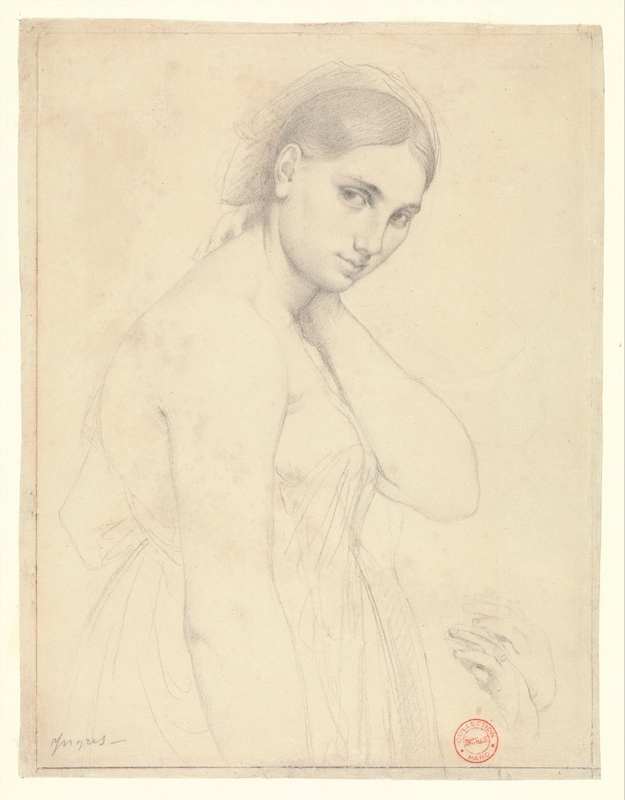

Dennis J. Martin - Deanna XXVI (1995), 24k gold and platinum on paper, Metalpoint

Lost and found edges can add greatly to the interest of a piece of art, not only in drawing. Many wonderful artworks are strengthened in this manner. Rembrandt, for instance, frequently used this method to anchor and enhance the atmosphere in a drawing, often in pen and ink and ink washes. These are just a few examples of his superb sense of darks and lights and their use and placement in the drawing.

Self-Portrait Etching at a Window , Rembrandt, (Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago)

Saskia Sleeping, Rembrandt

From a self-portrait to a small quick drawing of his wife, Saskia, sleeping, one of his wonderful lion drawings to studies of Women and Children, they all show his ability to merge the subject with the background in darks that anchor, meld and ground the subject.

Lion resting, turned to the Left, Rembrandt, c. 1650-52 .Louvre, Paris

A child being taught to walk; two girls, seen from behind, supporting the child on either side, a figure seated on the ground at left encouraging the child, a woman standing behind with a pail. c.1656, Pen and brown ink on brownish-cream paper., Rembrandt (Image courtesy of the British Museum)

Rembrandt - Saskia (”Woman Leaning on a Window Sill”)., between 1634 and 1635

Seurat was another artist whose consummate skill with atmospheric transitions from dark to light often involved the use of lost and found edges. His charcoals were especially famous for this. These are examples of a lady embroidering and another reading - intimate, shadowy drawings that evoke the dim light of a Parisian apartment, where edges are ill-defined and light falls fitfully (courtesy of the Fogg, Cambridge).

Embroidery, George Seurat, charcoal