When I recently saw the big Georgia O'Keeffe exhibition at the Tate Modern in London, I was rather disappointed. It seemed disparate, with a huge range in quality of her paintings, and the overall lighting was, I found, strangely cold and uninviting. Nonetheless, as always, there were marvellous gems. Predictably, for me, most of these special pieces were drawings done at various stages by Georgia O'Keeffe. It is always so interesting and important, I find, to see other people's drawings and theirdifferent approaches to creating a drawing: not only the actual materials used to make the marks, the size and presentation, but also the content, the emotions, the impact. Of course, being a drawing, each can potentially be much more direct and fresh, more unvarnished in honesty.

Read MoreDrawing

New Worlds: Spirit Drawings of Georgiana Houghton /

How many times do you go to an exhibition, especially in England, and end up talking to practically every other person in the room whilst looking at art? Not too often, I suspect! But that is exactly what happened as I went around a small and remarkable exhibition, "Georgiana Houghton: Spirit Drawings" at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Each of us was so astonished and fascinated that we all talked to each other at one point or another, standing in front of a drawing, all of us marvelling at these pieces.

Read MoreDrawing Trees /

Trees have always played a very important role in my life, ever since I learned to love all the diversity of tropical trees in East Africa. Baobabs, flame trees, jacarandas, grevilleas, mvule or African teak, thorn trees, and on and on. I was taught that all these trees were absolutely vital, for habitat, to help prevent erosion, promote moisture retention, enrich the soil and generally to enhance the world for allother species! In other words, trees are worthy of deep respect and merit great care. Artists have been some of the greatest admirers of trees. From early times, artists have drawn them, as portraits or in preparatory studies for paintings.

Read MoreWhen the Subject chooses the Artist... /

For a long time, I have found that in many instances, what I draw is seemingly dictated to me by happenstance. So when I read a quote from Maggie Hambling, one of Britain's leading figurative artists, about subjects choosing her, it resonated! She said, "I believe the subject chooses the artist, not vice versa, and that subject must then be in charge during the act of drawing in order for the truth to be found. Eye and hand attempt to discover and produce those precise marks which will recreate what the heart feels. The challenge is to touch the subject, with all the desire of a lover."

Read MoreThe Power of Line /

Ever since I started looking closely at drawings deemed “master drawings” in the first drawings exhibition held at the Louvre in 1962, I have been fascinated by the implications of the power of a line. No matter what period, Renaissance, Baroque, 17th or 19th century, the artist can say volumes merely by a line in a drawing. It does not even need to be a line that is perfect. Frequently lines that are re-drawn, adjusted and reinforced are extremely powerful and eloquent. The line can whisper and hint, it can assert, it can describe, it can evoke or imply. A line, in essence, can take on a life of its own, transmit it to the viewer and empower a dialogue between image drawn and the viewer that can be subtle and long-lasting.

Read MoreHokusai's Example /

When I was looking a the lovely collection of Hokusai's small and intense drawings in the Museum at Noyers sur Serein, I kept thinking about his enthusiastic approach to drawing. A brief quote of his about drawing, "Je tracerai une ligne et ce sera la vie", seems such a lofty goal to which to aspire as a draughtsman or woman. It stopped me in my tracks, because it implies such a deep, wide approach to making marks and creating a drawing. The quote in fact is part of a much larger and famous statement Hokusai made about drawing. Hokusai Katsushika, the long-lived and richly productive Japanese artist whose most famous series of woodcuts is probably the Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji, lived many iterations of an artist's life from his birth about 1760 to 1849. He drew obsessively.

Read MoreBurgundy Drawings /

Ammonites de Bourgogne, silverpoint, watercolour, Jeannine Cook

It is done – I have managed to produce 15 drawings for the exhibition at the Musée de Noyers! What a relief! I deliver them next Monday and the exhibition will run concurrently with the show I have hanging at the gallery at La Porte Peinte.

Preparing for an exhibition under deadlines is never a favourite occupation for any artist. However, some people do work best like that. I am not sure that I do – the results of the effort will be for others to judge!

What has been both interesting but also more complex has been the need to weave together a body of work that pertains to the ideas I put forward originally, namely the birth of metalpoint drawing in the scriptora of monasteries, where monks used lead to delineate the illuminations and trace lines for the script of their illuminated manuscripts. Combined with that history, I wanted to celebrate the tiny fossilized oyster shells found in the Kimmelridgian layers of soil found especially in the Chablis area and which contribute to the special terroir of those wines. I had picked up samples of these heavy stones when I first arrived in Burgundy last year, and they have led me on a fascinating odyssey.

Tying the metalpoint’s history together with the fossil-laden stones was thanks to those industrious monks who in medieval times also helped to spread the cultivation of wine, as they founded the great monasteries in Burgundy. Vezelay, Fontenay, Pontigny: they are all centers of such a rich heritage.

Even the wonderful and mighty plane trees, such as one sees at Fontenay that was planted in 1780 by the Cistercian monks, ten years before they had to leave their monastery, was part of that long-standing monastic heritage that enriches us all.

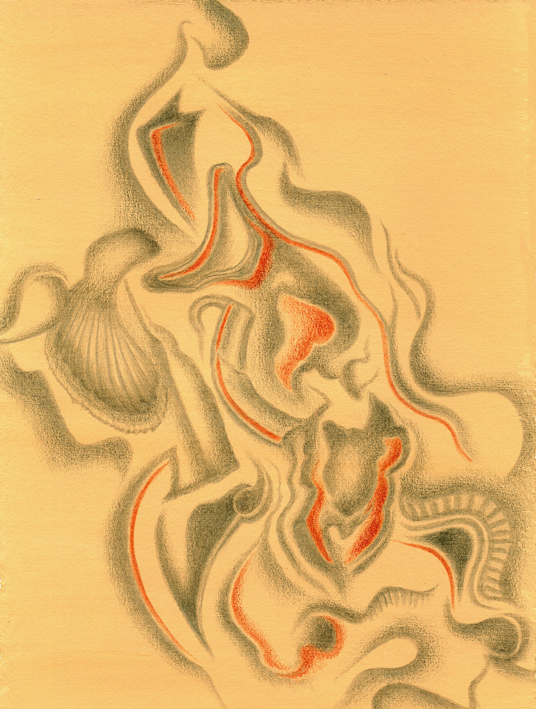

The other aspect that I tried to incorporate into these drawings is the close links between Burgundy and ocre, one of the key pigments in man’s artistic endeavours since the earliest marks man-made on cave walls from Australia to Africa to Europe. Burgundy was famous for its yellow ocre deposits and only ceased to produce ocre pigments in the 20th century. By heating yellow ocre, red ocre is produced; the two pigments find their way into every drawing and painting imaginable down the ages. I used the two colours as tinted grounds for some of the drawings I did for this project. Since early times, some artists used tinted grounds for their metalpoint drawings, so again, I was following a long-standing tradition.

I loved finding out all sorts of things about history and aspects of beautiful Burgundy for this project. It has been such fun - the drawings have been the perfect vehicle and excuse for all sorts of new insights and investigations. It is marvellous when art and fresh knowledge can go hand in hand.

Forms of Still Life /

Inching my way back from the roles of hospital companion and guardian to my husband as he recovered from an emergency operation, I finally felt I could slip back into my artist world a little. It was a welcome move as there is nothing more debilitating, for patient and family, than sojourns in a hospital. My first treat to myself was to see a recently opened small exhibition at the Museu Fundacion Juan March in Palma de Mallorca. Entitled "Things: The Idea of Still life in Photography and Painting", it straddled 17th century Dutch still life paintings and late nineteenth-early twentieth century photographs.

It was a really interesting premise, examining the forms of still life and even the cultural differences in the use of the word, "still life". The German and English versions of the words echo the original Dutch/Flemish concept of examples of things that are faithfully recorded in a carefully organised composition. But the Spanish "naturaleza muerta" or 'bodegon" stray far from the original premise. Most of the work presented represented northern artists, thus closer to the true sense of still life.

The Dutch paintings were lovely small ones, where the artists had delighted in the play of light on a glass goblet or a small ceramic dish, spoon or the crisp glint of a peeled lemon.

The leap to the early medium of photograph to record still life that, mostly, was pre-composed, was interesting. Sometimes, the photographs seemed airless, compared to the paintings, still a characteristic of many photographs today when compared to paintings. Yet there was an elegance and refinement in the photographs that were distinctive. As always, I seem to prefer the very simple compositions - such as one by Baron Adolphe de Meyer taken in 1908 of two hydrangea flowers in a glass of water, the reflections of the glass playing out on the wide expanse of the surface in the lower third of the photogravure.

The selection of photographic still life works was wide-ranging - from daguerreotypes to a coloured autochrome coloured back-lit plate of flowers by the Lumiere Brothers done in 1908, a circa 1895 trichromatic print of flowers (so much for all our modern "inventions" of technicolour) and then into the more modernist 1920-60 black and white work by Man Ray, Walker Evans, and many other European photographers.

Every interpretation of still life was there one could imagine - from carefully set up compositions, to views of life made still in abattoirs or after a volcanic eruption to Walker Evans spotting a natural still life scene on a back porch of a (sharecropper?) weather-beaten clapboard house.

As I looked at the different compositions and the elements that made up those compositions, mainly derived from nature, I could not help realising that most of my current artwork is, de facto, still life. I am using elements of nature in compositions that record stones, bark, flowers --stilled by being placed in a setting other than their original one. I have only strayed a little, like many other artists, from the path of still life "inventor" artists of the seventeenth century by cropping, zooming in on some elements and eliminating others, framing and thus altering the original concept and layout of the still life set up.

I love feeling this sense of kinship and heritage that comes when you look at artwork from previous times and understand how and why you do things the way you do, thanks to those earlier artists.

Video on Metalpoint and its Ins and Outs /

I have just received this video that video-maker Derek Gauvain made for me to celebrate metalpoint drawing. Check it out:

Wisdom from Dame Barbara Hepworth /

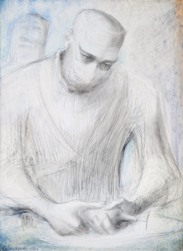

When I re-read a lecture that British sculptor, Dame Barbara Hepworth gave about 1953 to a group of surgeons, it seemed well worth repeating (courtesy of the Bowness, Hepworth Estate). Barbara Hepworth was a very good draughtswoman, and as a result of her daughter, Sarah, spending time in hospital in 1944, she became close friends with Norman Capener, a surgeon who treated Sarah at the Princess Elizabeth Orthopaedic Hospital in Exeter. He invited her to be present in operating theatres in Exeter and at the London Clinic, during surgical procedures, so that she could draw different scenes of the operations. As a result, she produced, between 1947-49, nearly 80 drawings of operating rooms in pencil, chalk, ink and oil paint on board. She became fascinated by the similarities between surgeons and artists, particularly with the rhythmic motions of hands.

She wrote, after being in the operating theatre in Exeter, "I expected that I should dislike it; but from the moment when I entered the operating theatre I became completely absorbed by two things: first, the co-ordination between human beings all dedicated to the saving of a life, and the way that unity of idea and purpose dictated a perfection of concentration, movement, and gesture, and secondly by the way this special grace (grace of mind and body), induces a spontaneous space composition, an articulated and animated kind of abstract sculpture very close to what I had been seeking in my own work."

In her c. 1953 lecture, she reiterated this unity of idea and purpose.

"There is, it seems to me, a very close affinity between the work and approach both of physicians and surgeons, and painters and sculptors. In both professions, we have a vocation and we cannot escape the consequences of it.

The medical profession, as a whole, seeks to restore and to maintain the beauty and grace of the human mind and body; and, it seems to me, whatever illness a doctor sees before him, he never loses sight of the ideal, or state of perfection, of the human mind and body and spirit towards which he is working."

"The artist, in his sphere, seeks to make concrete ideas of beauty which are spiritually affirmative, and which, if he succeeds, become a link in the long chain of human endeavor which enriches man's vitality and understanding, helping him to surmount his difficulties and gain a deeper respect for life."

"The abstract artist is one who is predominantly interested in the basic principles and unifying structures of things, rather than in the particular scene or figure before him."