When I recently saw the big Georgia O'Keeffe exhibition at the Tate Modern in London, I was rather disappointed. It seemed disparate, with a huge range in quality of her paintings, and the overall lighting was, I found, strangely cold and uninviting. Nonetheless, as always, there were marvellous gems. Predictably, for me, most of these special pieces were drawings done at various stages by Georgia O'Keeffe. It is always so interesting and important, I find, to see other people's drawings and theirdifferent approaches to creating a drawing: not only the actual materials used to make the marks, the size and presentation, but also the content, the emotions, the impact. Of course, being a drawing, each can potentially be much more direct and fresh, more unvarnished in honesty.

Read MoreExhibitions

New Worlds: Spirit Drawings of Georgiana Houghton /

How many times do you go to an exhibition, especially in England, and end up talking to practically every other person in the room whilst looking at art? Not too often, I suspect! But that is exactly what happened as I went around a small and remarkable exhibition, "Georgiana Houghton: Spirit Drawings" at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Each of us was so astonished and fascinated that we all talked to each other at one point or another, standing in front of a drawing, all of us marvelling at these pieces.

Read MorePainters' Paintings /

There is a really fascinating exhibition currently on display at the National Gallery in London:Painters' Paintings: from Freud to Van Dyck. The seed for this show was apparently the donation to the National Gallery of Lucien Freud's Italian Woman by way of the Acceptance-in-Lieu programme after Freud's death. Its arrival prompted the Gallery to investigate how many artworks in its possession had belonged to artists down the ages. The result of this inventory is this wonderful, interesting exhibition.

Read MorePoussin the Perfectionist /

I have always respected Nicolas Poussin's paintings, but often without really getting excited about them. They come across as resolutely independent, wonderfully composed and prepared, but often a little too intellectual for my taste.

Read MoreThe Old and the New, Religion or Art /

Every time you step into a museum, something new and fascinating swims into your consciousness. The magic happened again yesterday as I was in the most interesting British Museum exhibition, Sunken Cities, Egypt's Lost Worlds. Presenting amazing artifacts recovered from on-going underwater archeological work in the re-located sunken ports of Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus at the mouth of the Nile, the exhibition tells of the new insights into life in Egypt during the last four hundred years or so BC.

Read MoreWhen Art suddenly appears /

It is always fascinating to learn of how and when people become artists. It can be from early childhood, or even late in life - think Grand Ma Moses. Whatever the timing, it is always wonderful if that turn towards art is indeed so deep that the resultant art not only fulfills the artist but also enriches us all as viewers. I happened on an example of a young Parisian, a musician, who took up ceramics at the age of 24 and within four years, is producing amazing work. I was at a large, summer exhibition's opening at the Contemporary Arts Centre atthe Château de Tanlay in Burgundy, "Hommage à Bénin".

Read MoreAn Artist's Sense of Humour /

The name of the great 17th century French artisan , André-Charles Boulle, is synonymous with astonishingly complex marquetry veneers of woods, tortoiseshell, pewter and brass applied to elaborate furniture of huge value. I never expected to laugh out loud as I was viewing some of his work. I had always associated him with the work he created for Louis XIV and other illustrious French courtiers. He had been designated a master cabinet maker in 1666, by the time he was 24 years old; Louis XIV appointed him royal cabinetmaker in 1672, and he was a hugely successful artist.

The Wallace Collection has a large collection of his furniture, and each table, desk, wardrobe, chest of drawers is well worth studying closely. However, I soon decided that Boulle, for all his fame and wondrous skill in marquetery, must have had a sense of fun and humour.

Read MoreMuseum surprises /

Part of the fun of going to a museum is wondering what you are going to learn about that is totally unexpected and utterly fascinating. There is always something that stops one in one’s tracks. In London, I had huge fun recently learning about the most unusual and esoteric of objects in today’s context. How often does one use a tobacco grater today!

Tobacco had first been brought to Europe by Christopher Columbus and his men from Cuba, and by 1528, Europeans in general were being introduced to it, with an emphasis on all its medicinal advantages. The thriving trade helped foster colonization and was also an important factor in the slave trade with Africa. Sir Walter Raleigh supposedly brought the Virginia strain of tobacco to England in 1578 and again, its healthful aspects were emphasized. Virginia became a very important source of tobacco, with its cultivation spreading to the Carolinas. Tonnage imported to England steadily increased, and by 1620, 54,000 kg. were produced in Jamestown, Virginia, alone.

Read MoreThe Intensity of Size - Big or Small in Art /

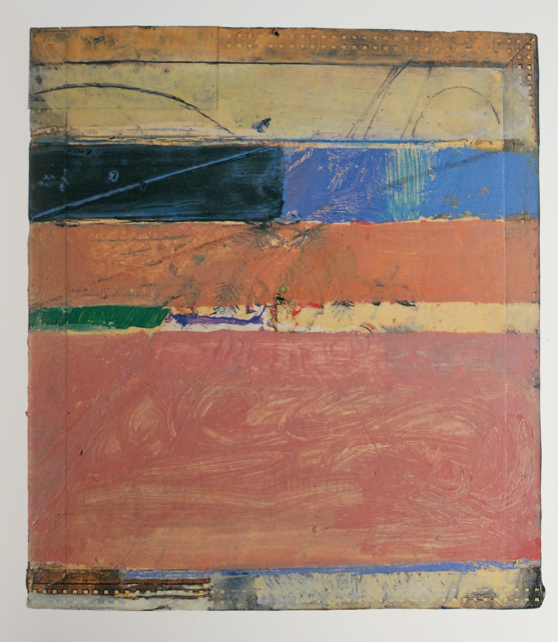

When I went to see the Richard Diebenkorn survey at the Royal Academy in London recently, I found it interesting but was surprised at my lack of excitement at seeing most of the work. The Ocean Park series on display were, of course, the most lyrical, but again, I was reminded of an internal conversation I frequently have with myself. Does a really big canvas manage to convey the intensity of the artist's passion? Or does the sheer size become, in many cases, a path to dilution of that excitement and energy? If you have to go on labouring day after day to paint huge surfaces, do you run out of steam? Of course, it is not always the case by any means — think of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, when Michelangelo laboured day after day in the most difficult of physical positions and conditions, and yet he achieved a power and impact of work that reverberates for every viewer.

Nonetheless, not every artist is a Michelangelo. And in the case of Richard Diebenkorn, I personally found that all his large canvases began to lack intensity. My reaction to these works was unexpectedly reinforced by three small paintings hung amongst the Ocean Park canvases.

They were three equally abstract works, painted on small cigar box covers. He used the cigar box cover paintings as gifts to friends, apparently, and my feeling was that these were the true gems in the exhibition. They were the perfect epitome of "small is beautiful". AsSarah C. Bancroft, curator of one Diebenkorn museum exhibition observes in the catalogue essay, they “capture one’s attention from across the room and command an expanse of wall space disproportionate to their actual size.”

Lyrical, free, certainly intense, but utterly lovely - they just sang. The more one explores the work Diebenkorn did in this small format, on cigar box lids, the more delightful and intimate the body of work becomes. Perhaps Diebenkorn felt liberated in this small format - he was not constrained by acres of canvas, nor the demands of gallery settings and collectors demanding impressive pieces. He could just create small delights that are intimate in scale, where his true sense of colour and the fitness of abstraction could be married to an acute sense of human celebration of life.

As Diebenkorn himself observed, "The idea is to get everything right — it’s not just color or form or space or line — it’s everything all at once." He certainly achieved that for me in the cigar box lid paintings.

The three large rooms of the Royal Academy's Diebenkorn exhibition were distilled down to these three small pieces, for me. In a funny way, they helped me feel more reassured about my own art - my frequent choice of small format in metalpoint drawings was strangely validated. I was grateful to Diebenkorn for that, but most of all, for three paintings that still sing to me weeks after seeing them.

Tiny Images, Vast Scenes /

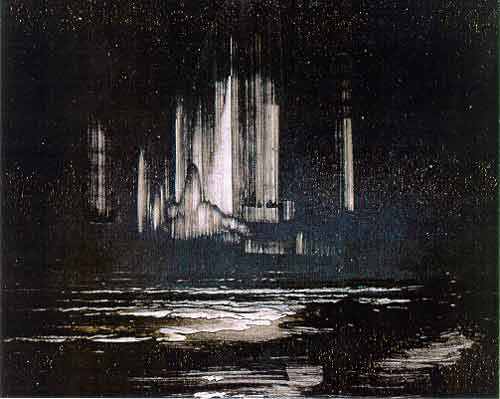

The Tempest, Peder Balke, 1862

Peder Balke is not the name of an artist that readily springs to mind, yet he is now considered the pre-eminent Norwegian artist of the 19th century. His landscapes and especially seascapes, highly unusual in their techniques, are now justly celebrated. I was lucky enough to see an exhibition of his paintings at the National Gallery, having seen a smaller one of his work in the same rooms four years ago. Balke lived from 1804-1887, started out as a full-time painter and then had to turn to other ways of earning his living. Nonetheless, he continued to paint, for his own pleasure, experimenting and using paints in ways that heralded modern expressionism. He travelled to the North Cape in Norway, an area of dramatic coastlines and radiantly strange light of the Arctic Circle. These scenes continued to influence him many years later. He did not always paint specific scenes, but used the moods and impressions of nature, often in almost abstract fashion, to convey the majesty, mystery, solitude and power of the natural world.

While the larger paintings on display in the National Gallery exhibition were impressive, especially the highly atmospheric ones of Northern scenes, done in the 1870s, the ones that fascinate me are the tiny ones. They pack a punch, almost in a visceral way.

They are indeed small, mostly blacks and white, seascapes and some landscapes of glaciers or waterfalls, often almost abstracts. They are not small, however, when it comes to impact. Their effect is perhaps more powerful than that of many of the larger paintings he did. Perhaps my love of monochromatic works leads me to them, but to me, they are stunning in their big voices coming from very small rectangles of oil on cardboard or oil on board.

I wonder if other people find them as arresting as I do?