Every artist is told - practice, practice, practice. But it is not always easy to do this, since life tends sometimes to get in the way. So finding a way to keep doing art is always important but nonetheless often challenging. However, I listened with interest to an interview done on NPR a couple of days ago by Rachel Martin. She was talking to famed photographer David Hume Kennerly about his new adventures with his iPhone 5 which he used as a camera. Having pared down his equipment to this one "camera", he set out to photograph the world around him in a very simple fashion, returning to basics of observation and curiosity. The resultant book, "David Hume Kennerly On The iPhone: Secrets And Tips From A Pulitzer Prize-winning Photographer", has just come out.

He set himself the challenge of going out into his neighbourhood and taking at least five photographs a day, trying to look at the familiar and perhaps even the trivial around him in a new fashion. It was a way to sharpen his skills and extend his powers of seeing. In other words, it was the perfect example of practice, practice, practice to improve as an artist. It was, as he described, his "photo fitness workout".

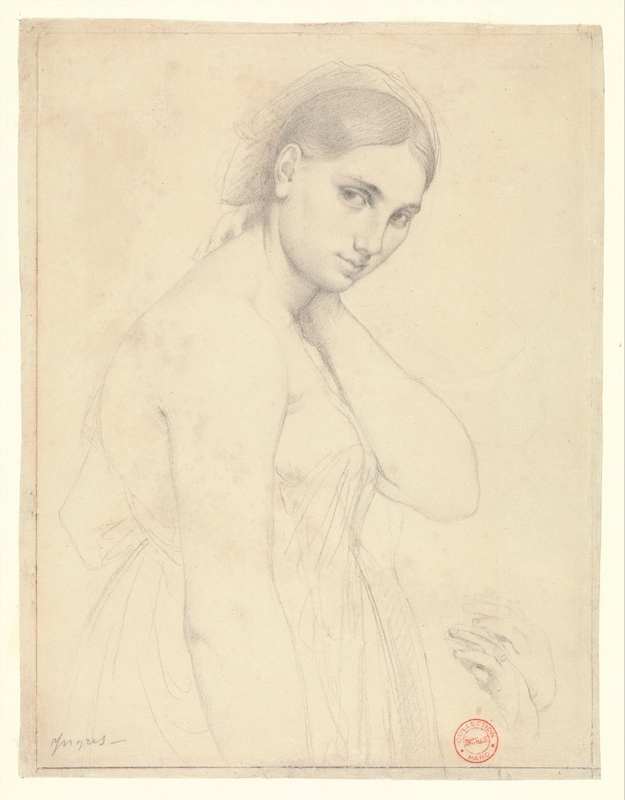

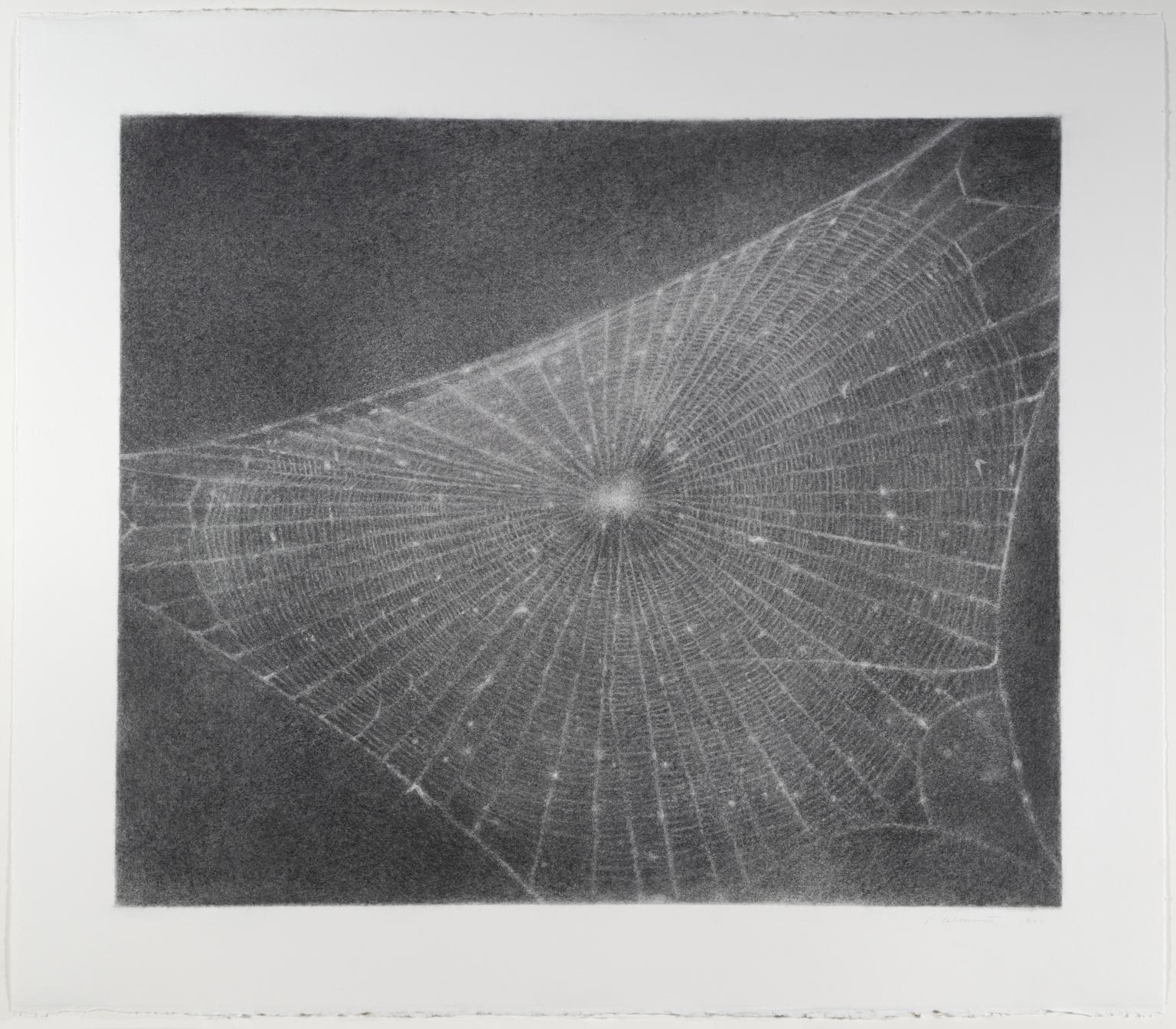

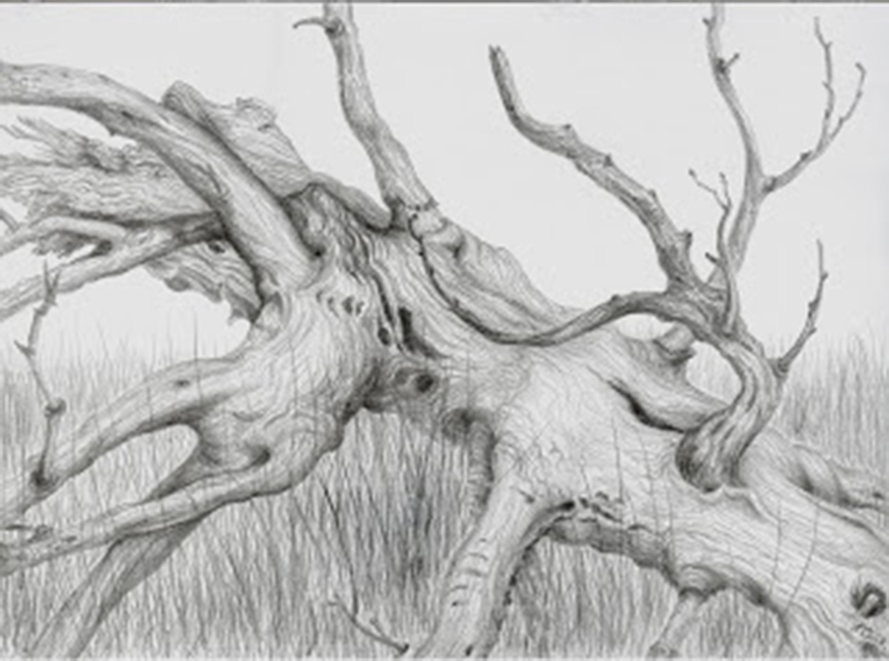

The parallel I made, as I listened to Mr. Kennerly talking - and remember, this is a revered photographer and Pulitzer prize winner talking - was the advice to go out with a simple, small drawing book and drawing tool. As a visual artist, I have always considered drawing to be the basis of understanding whatever it is that I am seeing in the world around me.

It takes seconds to make marks on a drawing book page - but whatever you are drawing then "belongs" to you. You know it, understand it better, remember it. It has become an integral part of you by the actions of mark making as your eye, brain and hand interact to record that simple object or sight. Countless artists, down the ages, have done this.

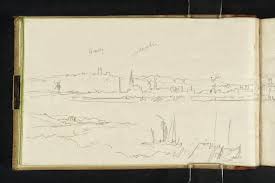

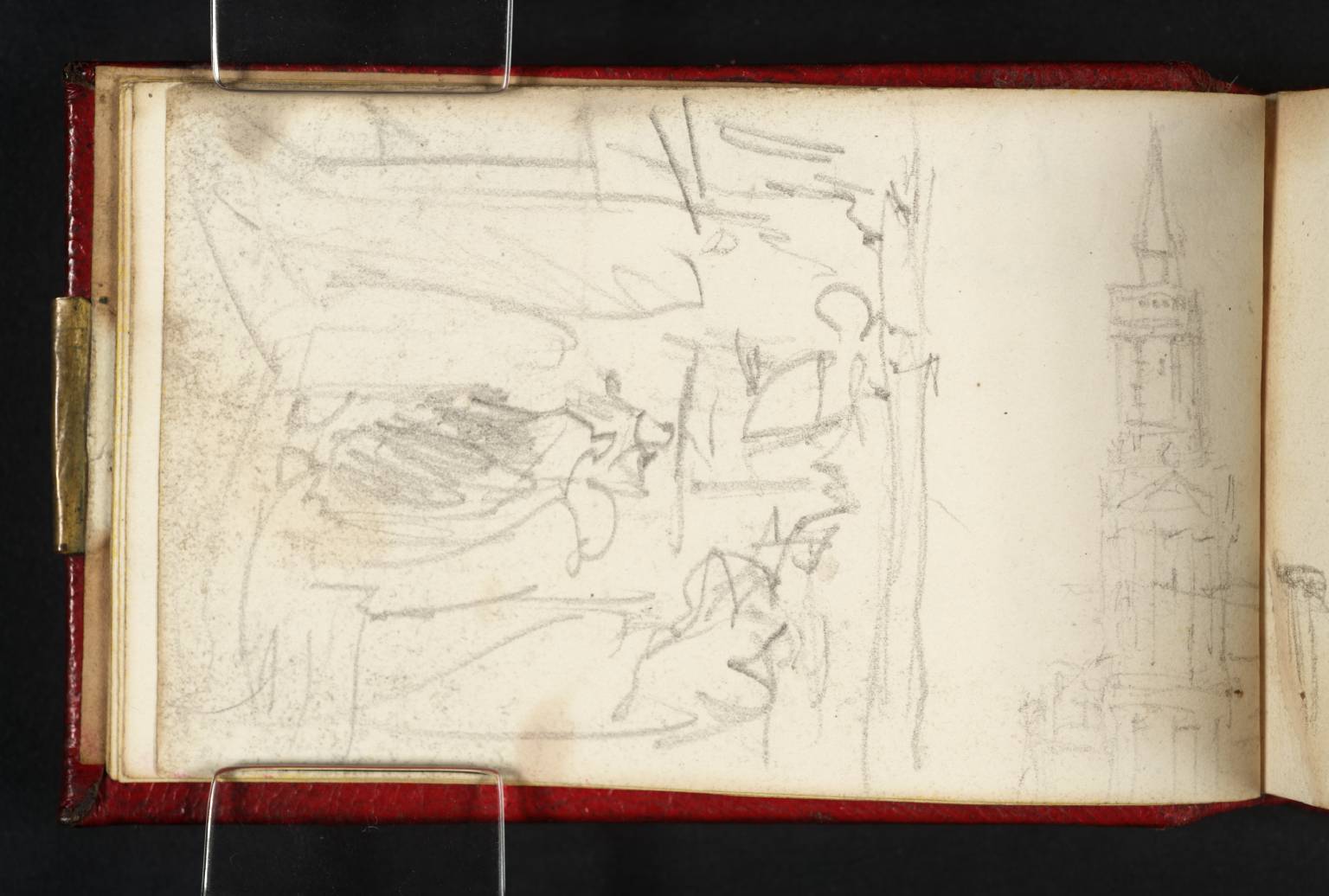

Having absorbed the image, it is then easier to edit and strengthen it, transmute it to something else. In other words, you can create art. Just as Mr. Kennerly created art through his simple medium of the iPhone, so each of us can use the image captured as the springboard to something else. Or just use the moment as a "limbering up", an exercice to keep eye/brain/hand coordination and skills. Just look at what Turner did in his wonderful sketchbooks.

Five quick drawings a day - a diary of one's voyage through life as you look around you, a record of moments of fascination and interest. And a way of remembering each day that your passion in life revolves around art.

Not a bad bargain to make. David Hume Kennerly's example is a wonderful one to follow for us all, in whatever version of art-making.