The exhibition, "The Hidden Cézanne; From Sketchbook to Canvas" is still on until September 24th, 2017, at the Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland. Cézanne's drawings, kept very private during his lifetime, tell of his questing, learning, thought processes in creating art or just recording for inspiration much later on. It reminds us all that drawing is a pathway to many ways of analysing, understanding and forging an artistic identity that is unique.

Read MoreEurope

Colour: Its Early Moral Strictures /

Learning about artists' strictures in the use of colour in antiquity and medieval times is fascinating and surprising, a far cry from today's total artistic licence in colour usage.

Read MorePlein Air Art - Looking Back (Part 3) /

In Part 3 of Plein Air art - Looking Back, I follow the development of plein air art during the late 18th and early 19th centuries in Europe as so many artists paved the way for present-day interpretations of nature and the outdoors.

Read MorePlein Air Art - Looking Back (Part 2) /

Part 2 of a long look back at the heritage of landscape and plein air art that we artists enjoy today nd from which we can draw encouragement and inspiration, as well as instruction.

Read MoreSilk /

Silk has always been my favourite material, sensuous to wear yet so practical and comfortable in all weathers. It is always beautiful, whether patterned, plain, embroidered or subtly woven with textures in it. Even its names - shantung, habutai, tussore, chiffon, taffeta, dupioni, tussah - sound exotic and alluring. One of my earliest connections with silk was the realisation that mulberry leaves, from a tree that I loved and knew well at my home in East Africa, were what feed the silk worms for 35 days, before they are ready to spin a cocoon with their continuous fine silken thread that eventually measures over a mile when it is carefully unwound, prior to being woven into cloth.

Read MoreThe Intensity of Size - Big or Small in Art /

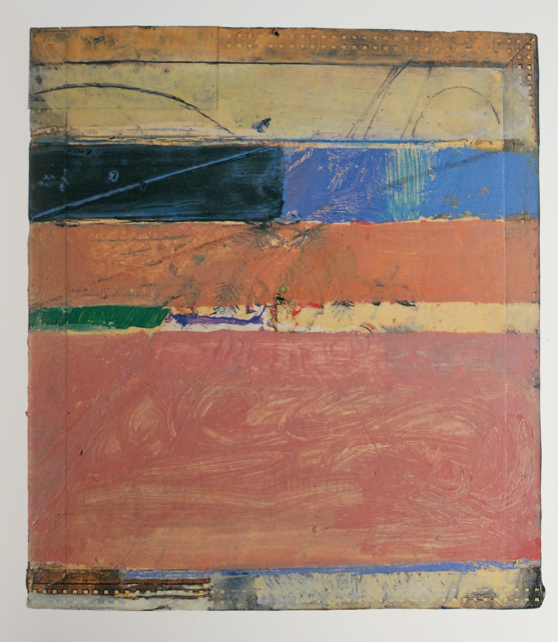

When I went to see the Richard Diebenkorn survey at the Royal Academy in London recently, I found it interesting but was surprised at my lack of excitement at seeing most of the work. The Ocean Park series on display were, of course, the most lyrical, but again, I was reminded of an internal conversation I frequently have with myself. Does a really big canvas manage to convey the intensity of the artist's passion? Or does the sheer size become, in many cases, a path to dilution of that excitement and energy? If you have to go on labouring day after day to paint huge surfaces, do you run out of steam? Of course, it is not always the case by any means — think of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, when Michelangelo laboured day after day in the most difficult of physical positions and conditions, and yet he achieved a power and impact of work that reverberates for every viewer.

Nonetheless, not every artist is a Michelangelo. And in the case of Richard Diebenkorn, I personally found that all his large canvases began to lack intensity. My reaction to these works was unexpectedly reinforced by three small paintings hung amongst the Ocean Park canvases.

They were three equally abstract works, painted on small cigar box covers. He used the cigar box cover paintings as gifts to friends, apparently, and my feeling was that these were the true gems in the exhibition. They were the perfect epitome of "small is beautiful". AsSarah C. Bancroft, curator of one Diebenkorn museum exhibition observes in the catalogue essay, they “capture one’s attention from across the room and command an expanse of wall space disproportionate to their actual size.”

Lyrical, free, certainly intense, but utterly lovely - they just sang. The more one explores the work Diebenkorn did in this small format, on cigar box lids, the more delightful and intimate the body of work becomes. Perhaps Diebenkorn felt liberated in this small format - he was not constrained by acres of canvas, nor the demands of gallery settings and collectors demanding impressive pieces. He could just create small delights that are intimate in scale, where his true sense of colour and the fitness of abstraction could be married to an acute sense of human celebration of life.

As Diebenkorn himself observed, "The idea is to get everything right — it’s not just color or form or space or line — it’s everything all at once." He certainly achieved that for me in the cigar box lid paintings.

The three large rooms of the Royal Academy's Diebenkorn exhibition were distilled down to these three small pieces, for me. In a funny way, they helped me feel more reassured about my own art - my frequent choice of small format in metalpoint drawings was strangely validated. I was grateful to Diebenkorn for that, but most of all, for three paintings that still sing to me weeks after seeing them.

Tiny Images, Vast Scenes /

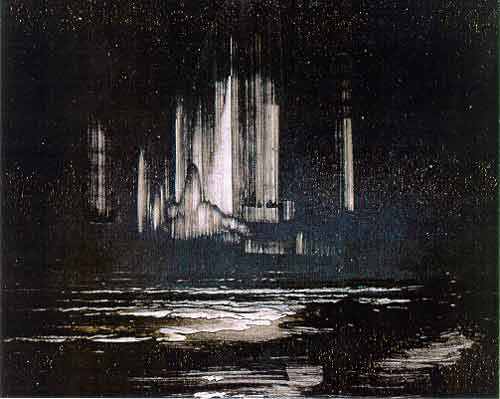

The Tempest, Peder Balke, 1862

Peder Balke is not the name of an artist that readily springs to mind, yet he is now considered the pre-eminent Norwegian artist of the 19th century. His landscapes and especially seascapes, highly unusual in their techniques, are now justly celebrated. I was lucky enough to see an exhibition of his paintings at the National Gallery, having seen a smaller one of his work in the same rooms four years ago. Balke lived from 1804-1887, started out as a full-time painter and then had to turn to other ways of earning his living. Nonetheless, he continued to paint, for his own pleasure, experimenting and using paints in ways that heralded modern expressionism. He travelled to the North Cape in Norway, an area of dramatic coastlines and radiantly strange light of the Arctic Circle. These scenes continued to influence him many years later. He did not always paint specific scenes, but used the moods and impressions of nature, often in almost abstract fashion, to convey the majesty, mystery, solitude and power of the natural world.

While the larger paintings on display in the National Gallery exhibition were impressive, especially the highly atmospheric ones of Northern scenes, done in the 1870s, the ones that fascinate me are the tiny ones. They pack a punch, almost in a visceral way.

They are indeed small, mostly blacks and white, seascapes and some landscapes of glaciers or waterfalls, often almost abstracts. They are not small, however, when it comes to impact. Their effect is perhaps more powerful than that of many of the larger paintings he did. Perhaps my love of monochromatic works leads me to them, but to me, they are stunning in their big voices coming from very small rectangles of oil on cardboard or oil on board.

I wonder if other people find them as arresting as I do?

Dutch Utopia exhibit at Telfair Museum /

Savannah's Telfair Museum of Art has just opened an unusual and most interesting exhibition, Dutch Utopia. Using art already in the Museum's permanent holdings as a springboard, curator Holly Koons McCullough and her team have assembled a large number of works by American artists who worked in artists' colonies and small unspoiled villages in the Netherlands during the second half of the nineteenth century.

There are plenty of canvases large and small by artists who remain well known today, from John Singer Sargent to Robert Henri and William Merritt Chase. Then there are the delights to be savoured thanks to many artists whose names are less familiar today, from George Hitchcock to accomplished women artists like Anna Stanley and Elizabeth Nourse. Traditional compositions of landscape or interiors suddenly change to daring works which feel much more contemporary to us today. Watercolours hold their own with oils on canvas, some huge. It is an interesting mix of works and takes one to a totally different time and place, in a tight society living beneath amazingly luminous Northern skies, where wind and sea dictate every aspect of life and, according to one contemporary comment, there is a great deal of the colour blue in sunlight. The American artists lived there for varying lengths of time, but they all seemed to concentrate on eliminating from their work any hints of the changes that Europe had been undergoing as the Industrial Revolution reached its zenith. The Holland they portray had barely changed from the work Rembrandt and Franz Hals knew.

I found myself contrasting many of the scenes of Dutch women, be-coiffed and be-clogged, monumental and utterly Northern, with those by the Pont Aven school of artists who were depicting the Breton women with their typical coiffes and, yes, clogs too, on occasion. Working at about the same time, Gaugin, Sérusier, Emile Bernard and a host of other French artists were working in the sleepy little Brittany towns of Pont Aven or Le Pouldu. They were, to my eye, far more adventurous in their approaches than the Americans in the Netherlands, but each community produced some wonderful art.

The Ghost Story, 1887, Oil on canvas, Walter MacEwen , (Image courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio)

In Holland, 1887,Oil on canvas, Gari Melchers

Gari Melchers Home and Studio, Fredericksburg, Virginia

The Telfair's exhibition runs until January 10th, 2010, before moving to the Taft Museum of Art in Cincinnati, the Grand Rapids Art Museum and the Singer Laren Museum in the Netherlands.

It is well worth seeing at one of its venues.