A series of coincidences in recent months, as I learn about different aspects of the colour blue, culminated in a wonderful, thought-provoking exhibition, “Blue - The Colour of Modernism”, currently on display at the Caixa Foundation in Palma de Mallorca. The palette of blues increased vastly in the later 19th century, and artists evoked innumerable emotions and situations with their skilful use of different shades of blue, a colour which hallmarked that era to a great degree.

Read MoreLandscape

Belonging to Country - a Western Australian Artist /

Lance Chad, Tjyllyungoo, a Nyoongar Aborigine artist, exhibiting in Perth’s Western Australian Art Gallery, reminds us of our vital spiritual and literal connections to County and Land. We all belong somewhere, and the underpinning natural landscapes that have sustained generations of humans, animals and plants are ever more vital to us all. Lance Chadd’s art is a wonderful tonic and incentive to think and, ideally, celebrate our world.

Read MoreA Passion for Drawing /

Three exhibitions in New York, each by a superb artist in a different century, but all united by a lifelong passion to draw, draw, draw, anything and everything. For an artist, these current exhibitions are a wonderful reaffirmation of the central role drawing potentially plays in the development and creativity of an artist. Gainsborough, Delacroix, Wayne Thiebaud - three very dissimilar artists, yet they are all on the same page in a drawing book.

Read MoreRecurrent Themes in An Artist's Work /

Olive trees are an integral part of the Mediterranean landscape, and they have been a recurrent theme in many artists' work. Sacred trees since early Greek times, they are astonishing in inspiration, as well as generous in their fruit and oil. No wonder artists love to celebrate these astonishing and often very ancient trees.

Read MoreChoices in an Artist's Life /

Friend of many of the prominent Impressionist painters, as well of being in Edouard Manet's circle, artist Norbert Goeneutte was a discovery for me when I saw one of his paintings recently at the National Gallery in London. His career choices were interesting.

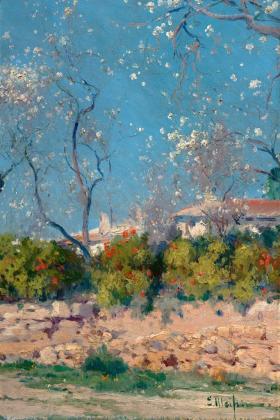

Read MoreAlmond Blossom - a Joy for Artists /

January and February in Mallorca, Spain, are months of delight for those of us who love almond blossom. The island is transformed into fairyland, with row upon row of pink and white blossom undulating through the valleys and over the plains, always with the backdrop of dramatic blue-green mountains and azure winter skies. Beneath the trees lie carpets of emerald winter wheat sprouting or grazing land that is dotted with huge herds of shaggy sheep, often with early fragile lambs. The incredible winter light playing over the blossom is crystalline and renders every detail vivid and gem like.

Almond blossom not only plays an important role in ensuring the production of almonds, always an important crop, and a major tourist attraction in Mallorca; it has also inspired many artists. Perhaps the most famous among these artists were those of the 19th and early 20th century, many of them from Catalonia, who visited the island and were captivated by the island landscapes and. above all, the light here. Even Joaquin Sorolla exclaimed, "This light, this light, it is impossible to capture it!" ("Esa luz, esa luz, es impossible capturarla!").

One of the most famous of the Catalan painters who became one of Mallorca's leading landscape painters was Santiago Rusiñol i Prat. He was also a noted writer, poet and playwright. Born in 1861, he came first to Palma in 1893. After spending time in Paris, he returned to Mallorca in 1901, partly to get over a drug addiction. From then on, he spent a great deal of time on the island, celebrating its scenery, gardens and flowers. In 1912, he also published La Isla de la Calma, a paen to the Island of Calm, Mallorca, that he believed was a bulwark against the increasingly frenetic industrial and materialistic world elsewhere.

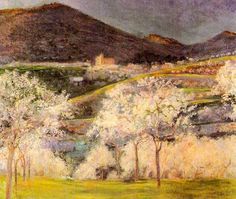

Terraced Garden in Mallorca, Santiago Rusiñol, 1904

Santiago Rusiñol was often accompanied by artist friends during his stays in Mallorca. Joaquin Mir (1873-1940) was one of his companions, and lived for four years in Mallorca from 1901 onwards, often in the north of the island around Pollensa.. He became known as the father of Mallorcan impressionism, having evolved from an early much more personal approach to painting, when he merged form and colour. Mir too fell under the spell of the springtime almond blossom around the island.

His early paintings of spring differ greatly from his later work, but all sing of Mallorca's light and extraordinary beauty that comes in January and February.

Another of Santiago Rusiñol's friends in Paris and Barcelona was Eliseu Meifrèn i Roig, (1857-1940), a Catalan who travelled widely and was highly respected for his plein air approach to landscapes. He too came to Mallorca as the new century dawned; ultimately he became director of the Art School in Palma in 1910. His paintings of almond blossom are lyrical.

Eliseo Meifrén taught another Palma-born artist who became very well known for his paintings of Mallorca, Joan Fuster Bonnin (1870-1943). Talented and prolific, he was friendly with Santiago Rusiñol and Mir, and later, with another very successful artist in Mallorca, Anglada Camarasa.

How many paintings can one appreciate of almond blossom? I don't know, but I do know that the late 19th and early 20th century saw an amazing number of artists tackling paintings of these almond trees in flower. Incidentally, these blossoms are rather short-lived, for winter winds and rain play havoc with them, and within the space of a week, the tender brilliantly green pointed little leaves begin to replace the pink or white blooms.

Another four examples of artists who loved Mallorca in January and February. Take your pick!

Perhaps the suitable footnote to all the artists' paintings of Mallorca's almonds and the light in which they sparkle is to add the fact that almonds are the earliest domesticated tree nuts, originating in the Levant and spreading through the Mediterranean basin. It is thought that almond trees were first introduced to Mallorca during the Roman times, after Quinto Cecilio Metelo conquered the Balearic Islands in 123 BC. When grapes were so badly affected by phylloxera towards the end of the 19th century, the Mallorcans planted almonds as a replacement crop. Thus the Catalan and Mallorcan artists had such wonderful panoramas of almond trees in flowers to delight and inspire them.

Abstract Organisation /

Thinking further about composition and the fact that the path to achieving a successful painting or drawing often takes one into abstraction reminded me of a quote that I had found by British painter, Royal Academician and art professor at St. Martins, Frederick Gore. He was writing about abstract art back in the mid-fifties, rather against the tide of art in England at the time. He remarked, "The meaning of a figurative work of art lies in its abstract organisation."

Late Evening Looking towards the Crau, Frederick Gore (image courtesy of John Adams Fine Art Ltd.)

During his long and productive life, Gore produced a huge body of work, often working en plein air, and frequently travelling to different parts of the Mediterranean region. It is interesting to look at examples of his work to see how he used abstract organisation to compose his paintings, and thus allow their meaning and impact to be strengthened.

Above, Late Evening Looking towards the Crau shows this abstract underpinning: wedge shapes are counterbalanced by thrusting mounds that echo each other through the painting, each shape linking in subtle fashion with the next.

Paysage du Luberon, Frederick Gore, (image courtesy of Charlotte Bowskill Fine Art)

Paysage du Luberon, another painting done in France (image courtesy of Charlotte Bowskill Fine Art), shows the same strong abstract organisation. Gore used not only the different shapes to form an abstract pattern but he used colour to lead the eye through the picture. This painting is a wonderful example of what American watercolour artist and teacher, Edgar Whitney, always talked about, namely, that a strong shape in a painting is "irregular, unpredictable and oblique".

Puig Mayor from Fornalutx, near Soller, 1958, Frdereick Gore, (image courtesy of the British Government Art Collection)

Another painting, done in Mallorca of Puig Mayor from Fornalutx, near Soller, uses the shapes of the olive trees to organise the painting, with the distant mountains echoing the clumps of trees. As a counterbalance, Gore used the wonderful orange-yellow-russet fields to pull one through the whole composition.

Landscape near Deya 1958, Frederick Gore,(image courtesy of the British Government Art Collection)

In an even more brilliant depiction of Mallorca, also done in 1958, Frederick Gore painted this Landscape near Deya. He organised the canvas into four main abstract forms and one smaller one, always a powerful way of dealing with a composition. The olive trees again lead one into and around the painting. The abstraction allows total coherency in what Gore was meaning to say about this hot, sunlit Mediterranean mountainside.

On a more personal note, I always love seeing how other artists respond to the landscapes of Mallorca, an island I know and love deeply. Despite the more than fifty years since these two paintings were done, this part of Mallorca is not that dramatically changed, something to be celebrated.

Frederick Gore certainly put into personal practice what he advocated. It is good to remind oneself of how to organise an eloquent, powerful work of art through abstraction.

Landscape Painting /

Back in March of this year, in The Spectator, Angela Summerfield discussed Peter Frie:Last Summer, an exhibition of landscapes by a Berlin-based Swedish artist, Peter Frie. In view of the fact that tomorrow, I am planning to work plein air on landscape drawings, this statement in Summerfield's article came back to me.

I quote, "Landscape painting has not fared well within the dictates of modernist and post-modernist art definitions. It is as if an urban-centric, text-driven and often anti-aesthetic dogma has stifled both alternative discourse and individual human expression. Yet our experience of landscape, and by association Nature, is fundamental to the development of our senses, perceptual vocabulary and cognitive awareness.

Eliopainting No. 3 Peter Frie, oil on canvas, (image courtesy of Eskilstuna Konstmuseum.)

This statement resonates for me in a number of ways. Since I live in non-urban environments, I find most of my daily delights and inspiration in Nature, in one way or another. I am also very aware that my tastes are therefore different from those of countless millions of people who live in big cities, where the dragooned green trees along streets and in artificially-constructed parks are the major remnants and reminders of the natural world, apart from weather conditions.

The world in which we all live is indeed mostly text-driven, a fact which again contributes, according to this thought-provoking book that I am reading, Moonwalking with Einstein, by Joshua Foer, to our collective loss of the capacity for memory. Because we can all rely on books, Google, digital files or whatever to recuperate facts, our memories have virtually abdicated, as compared to the memory of Greeks, Romans and medieval notables.

In those early times, people could remember vast amounts of knowledge, from all the names of soldiers in an army to long, involved speeches or treatises. After Gutenberg invented the printing press in 1436, our memories took a hit. In the same way, only well-trained artists retained the capacity to remember innumerable details of landscape or human form. Familiarity with landscapes and Nature's ways became the domain of the few in the art world.

Today, that is indeed true. Yet unless we artists somehow learn how Nature "works", an enormous chunk of our personal vocabulary is stunted. It is as if we try to learn French, but never hear how the words are correctly pronounced. We thus never understand the nuances, the cadences and accentuations, let alone the words themselves, that convey a world of meaning.

Ultimately, I fear that Angela Summerfield's rather pessimistic outlook about landscape painting will continue to pertain. I don't see art collectors returning en masse to support landscape painting (and drawing). Nonetheless, for those of us who believe landscapes and Nature in general have much to offer, there is the comfort that personally, we are enriched, and that there are indeed some people with whom landscape painting resonates. Hurray for "alternative discourse and individual human expression"!

Peter Frie's version of a "Blue Morning" (image courtesy of artfinders.co.uk.)

Just look at Frie's Blue Morning. He should give us all encouragement and hope to follow our own paths vis-a-vis Nature.

Artists' Ways of Seeing Things /

I am reading a book entitled "Moonwalking with Einstein. The Art and Science of Remembering Everything" by Joshua Foer. The title is self-explanatory, the style is highly readable as Foer is a seasoned writer for such publications as the New York Times, National Geographic, Slate, etc. The content is totally fascinating - about how science is slowly understanding better how the human brain works, especially in terms of memory.

I still have many pages to go, but one page started me thinking about the parallels between artists and the master chess players that Foer was discussing. In the 1940s, Adriaan de Groot, a Dutch psychologist and chess player, decided to investigate what separated a good chess player from a master chess player - what was going on in their heads? Were the top players able to think further ahead in their moves, did they have better mental tools or a more honed intuition for the game? From past high level games,De Groot selected a series of board positions where there was one correct move to make which was not all that obvious. He then asked a group of top flight chess players to ponder these boards and to think aloud as they selected the proper move.

To De Groot's astonishment, the players mostly did not think many moves ahead, nor did they consider more possible moves. What they did was to see the right move, and almost immediately. After analysing the players' commentaries, De Groot realised that the chess experts were reacting, rather than thinking, and they could do this because their long experience of playing had taught them to think about "configurations of pieces like 'pawn structures' and immediately noticed things that were out of sorts, like exposed rooks". They had learned to see the whole chess board and thirty-two chess pieces as systems and groups. Later studies of top players' eye movements confirm that they literally see a different chess board, for they see more edges of the squares, which means they are encompassing whole areas at once. They also move their eyes across greater distances, without lingering for long at any one spot. Those places on which they do focus tend to be the key areas linked to making the right move.

This description of how master chess players function made me think of artists who have honed their skills day after day, year after year. Their eye-hand coordination has been perfected, their senses of composition/design, colour and content are developed. When they draw a nude, for instance, or work on a landscape painting plein air, for instance, they are not looking at just one spot. Rather, they are encompassing the whole so that almost intuitively, they can adjust their composition, their values and colour in the work for the best results. Their powers of observation and concentration are almost unthinking, because they are trained and disciplined.

The Red Canoe, 1889, watercolour, Winslow Home (Image courtesy of the Peabody Art Collection, Baltimore, Maryland)

To me, Winslow Homer is an example of a highly skilled painter, producing amazingly fresh landscapes, frequently plein air, and often in watercolour. One such example is "The Red Canoe" (image courtesy of the Peabody Collection, the Athenaeum).

Foer goes on to comment on the master chess players' amazing memories. I suspect that the great artists, past and present, also intrinsically rely on their memories quickly to understand a subject after a brief moment of studying it, Like the chess players, they can also call upon past experiences to bolster and inform their present work. The saying, "Been there, done that" applies, in a very positive sense, to an artist as well as chess players. Perhaps one should just add, "umpteen times"!

Landscape Painting and Politics /

There has been a small but fascinating exhibition tucked into the National Gallery rooms in London. "Forest, Rocks, Torrents. Norwegian and Swiss Landscape Paintings from the Lunde Collection" had just opened when I saw it in late June but it runs until the 18th September.

Two rooms, but expansive views of Norwegian and Swiss mountains, rivers and dramatic natural scenery that take one far away from the tourist-filled Trafalgar Square outside. It was a collection of small and beautiful paintings assembled by Asbjorn Lunde, a major art collector/lawyer from New York. Not only did this exhibition of art delight and inform, but it made me think about the role of landscape painting in national politics and national identity. This was mainly because of a fascinating and informative piece, "Two Traditions", in the catalogue written by Christopher Riopelle. Curator of post-1800 Painting at the National Gallery.

Ancient Rome celebrated its landscapes in frescoes, such as those which survived from Pompeii. However, in the Western art tradition, basically relgious motifs and classical narratives provided the major impetus for painting themes and subjects until the 17th century. At that time, the Dutch begain to celebrate their flat, luminous countryside, where the northern light and ever-present sea predominated. They had regained control of their land (and church) from the Spanish and by the 17th century, Holland was linking political identity with the Dutch landscape. In fact, the very word landscape, used in relationto painting, comes from the Dutch language, where landschap first meant a cultivated patch of land and then an image.

View of Harlem with Bleaching Fields, 1670-75, Jacob van Ruisdael, (Image courtesy of Kunsthaus Zurich)

Jacob van Ruisdael was a major protagonist of Holland's land and wide skies in his art in the 17th century, as one can judge in this "View of Harlem", above. Much of this landscape art was produced in studio after plein air studies had first been done.

Salomon van Ruysdael specialised more in maritime scenes, but he too represented the Dutch landscape in remarkable fashion.

The River Scene, Salomon van Ruysdael, 1632(image is courtesy of the National Gallery.)

These and many other artists were projecting the new self-confidence of a successful maritime nation whose trading stretched across the globe and brought home great wealth. These relatively small landscape paintings were bought by the affluent burghers as part of this new national celebration.

The same phenomenon occurred in Britain in the 18th century as the landed gentry and newly-affluent townspeople started to identify with their green, gentle island whose power was spreading far abroad. There were many great landscape artists working then, and even those more famous for portraiture, such as Thomas Gainsborough, were meeting this demand for landscapes. His 1748 "Landscape in Suffolk" is one such example. In subsequent decades, John Constable and J.M.W.Turner, amongst other artists, also allowed the English to be proud of their island, its landscapes, people and history, through their paintings.

Landscape in Suffolk,1748 Thomas Gainsborough (courtesy of the Kunsthistorisches Museum),

Harwich Lighthouse, c. 1820, John Constable (image courtesy of the Tate)

Constable painted this canvas of "Harwich Lighthouse" about 1820. His renditions of skies and clouds show the results of his many, many wonderful cloud studies and knowledge of Britain's climatic conditions.

Turner was equally attentive to light and climate as he painted, as can be judged by this astonishing canvas from 1816, "Chichester Canal". Apparently, the Indonesian volcano, Mt. Tambora, had erupted very violently in 1815, and the ash travelled around the world, causing dramatic atmospheric conditions. The 3rd Earl of Egremont commissioned the painting.

Chichester Canal, Joseph Mallord William Turner circa 1829 (Image courtesy of the Tate Collection).

While the British, the Russians, the Swiss, the Norwegians and other Europeans were identifying increasingly with their nations, thanks in large part to artists' depictions of the natural wonders and characteristics, the Americans were doing the same. As the Hudson River School, the Romantic and Luminist schools of landscape painters developed in the United States, the paintings of the country's natural splendours helped fuel the sense of nationhood and drive towards development of the West. Even the eventual creation of National Parks was made easier by the depictions of the marvels of Yosemite and Yellowstone. Manifest destiny was implicit in much of the 19th century landscape painting in America, where discovery, exploration and settlement were all driving forces in society.

The Oxbow. View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Mass. after a Thunderstorm", 1836, Thomas Cole , (Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

British-born American artist Thomas Cole was the founder of the Hudson River School; he introduced the beauties of the Hudson River Valley, the Catskill Mountains and upper New York/New England to an audience of appreciative fellow Americans. Second generation American landscape painters who continued to shape the political framework of America included such artists as Luminist John Frederick Kennsett. His work centered on the North East, but included work depicting the Mississippi and further afield.

Lake George, ca. 1860,John Frederick Kensett (1816–1872)

Oil on canvas, 22 x 34 inches (approx.)

Collection Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain,

Thomas Moran, meanwhile, was celebrating the wonders of the West. His depictions of Yellowstone were hugely instrumental in the National Park being created. His dramatic canvases were complemented by watercolours of many natural phenonmena, such as this 1873-74 watercolour of the "Shoshone Falls, Idaho" (image courtesy of the Chrysler Museum of Art).

Shoshone Falls, Idaho, 1873-74, thomas Moran, (image courtesy of the Chrysler Museum of Art).

All these landscape artists, European, Russian, American... were part of an ever-swelling political discourse about national identity and aspirations. The 18th and 19th centuries were era of great social upheavals and changes, with the Industrial Revolution shaping new societies. With increasing urbanisation, the role of landscape underwent a subtle change: it was no longer such an important defining factor in perception of nation. Artists themselves were often urban dwellers who had to make trips to the countryside to paint landscapes. The French Impressionists built on this tendancy that the previous generation of artists had begun - from Daubigny to Millet and Rousseau. Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, and their companions all made trips out from Paris in their early times as artists. But they also found increasing inspiration in urban scenes - railway stations, the French boulevards, the Seine river. As the artistic trends evolved, Picasso, Braque, Juan Gris, Matisse and countless others began to turn away from landscape painting. There were, of course, others - Cezanne, the Fauves, Miró - who still used the vocabulary of landscape to explore the role of man in society.

Nonetheless, I can't help wondering how much the influence of urban landscapes - concrete and stone boxes and towers, streets vanishing in distant perspectives, the geometry of man's creations - overwhelmed the artistic eye as the trend accelerated towards abstraction and away from organic natural shapes and scenes. With such a different artistic vocabulary, has our societal identification of land and nation altered? Even though today's world is saturated with high definition images of amazing landscapes, do we identify with our lands in the same way as people did in previous centuries with their artists' depictions of land/nation? Do we find it easier to airbursh/Photoshop ourselves out of involvement with the landscapes we are filling up and polluting and exhausting today? Easier than when we were being shown the beauties of our lands by artists who were, in essence, pictoral ambassadors for those splendors? Indeed, basically, the majority of today's populations live in some form of urban setting, where concrete obliterates the natural world and where political perceptions have been altered by those surroundings.

Today's landscape artists have a very different role, I suspect, from the nation-building one of the Dutch artists onwards. Now, perhaps, it is almost a rearguard action or one of recording natural beauties before they disappear. However, I have grave doubts as to whether any of today's landscape artists, seldom ones who make the headlines in the art world, have much sway amongst our politicians. Perhaps it would make society better if they did?